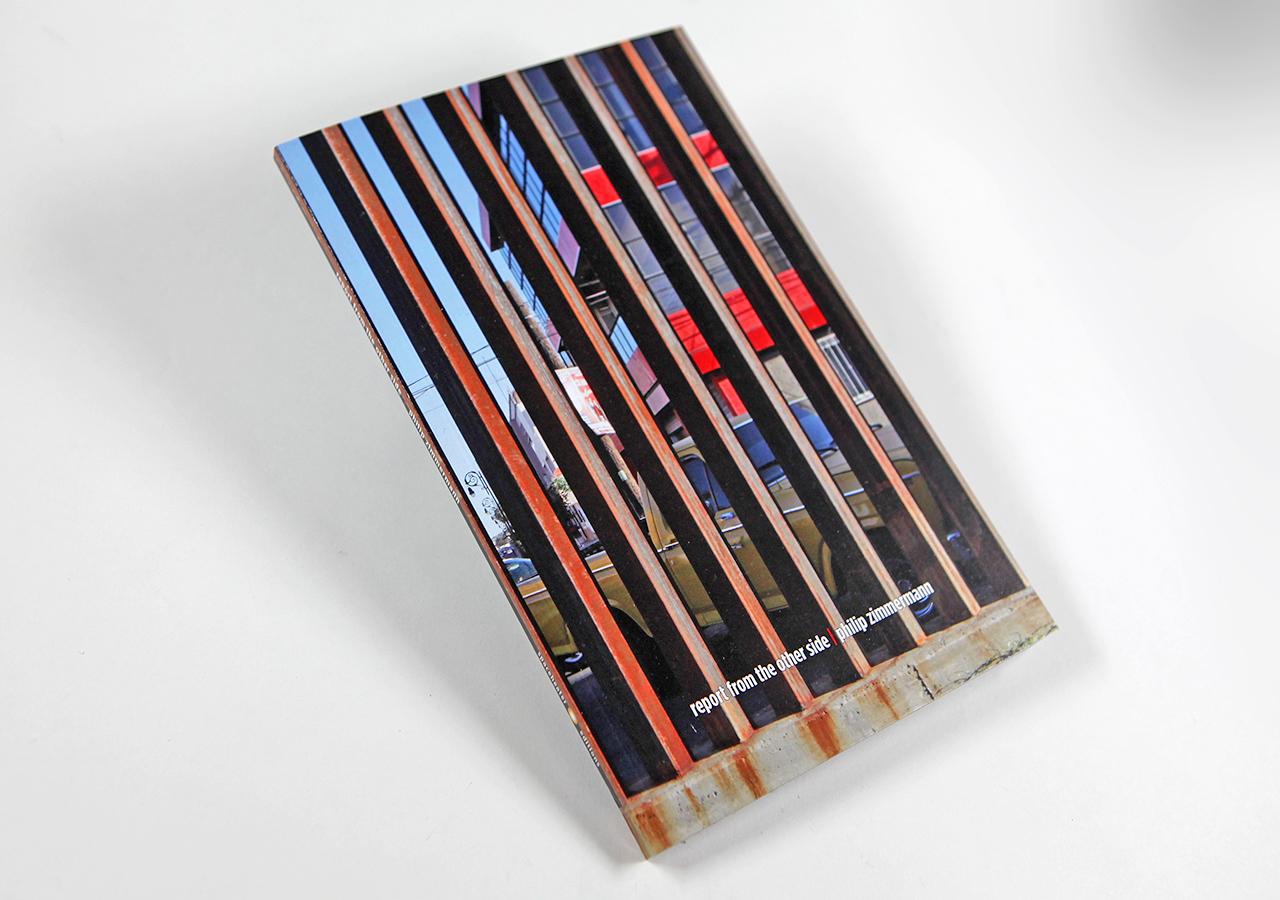

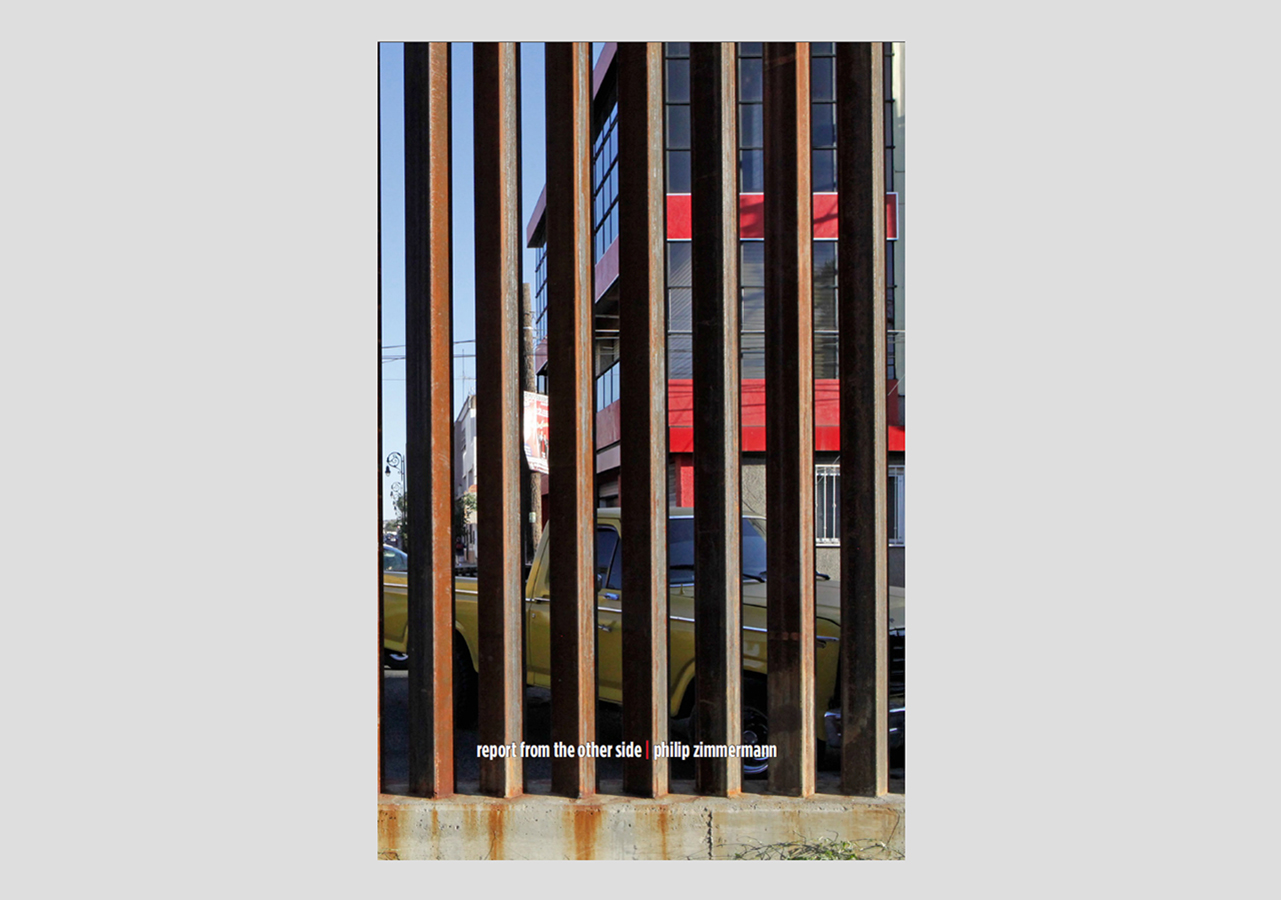

REPORT FROM THE OTHER SIDE Philip Zimmermann (2013)

REPORT FROM THE OTHER SIDE by Philip Zimmermann is a contemplation of the human impulses behind building barriers and fences separating different peoples and cultures. What follows is much of the text from the book:

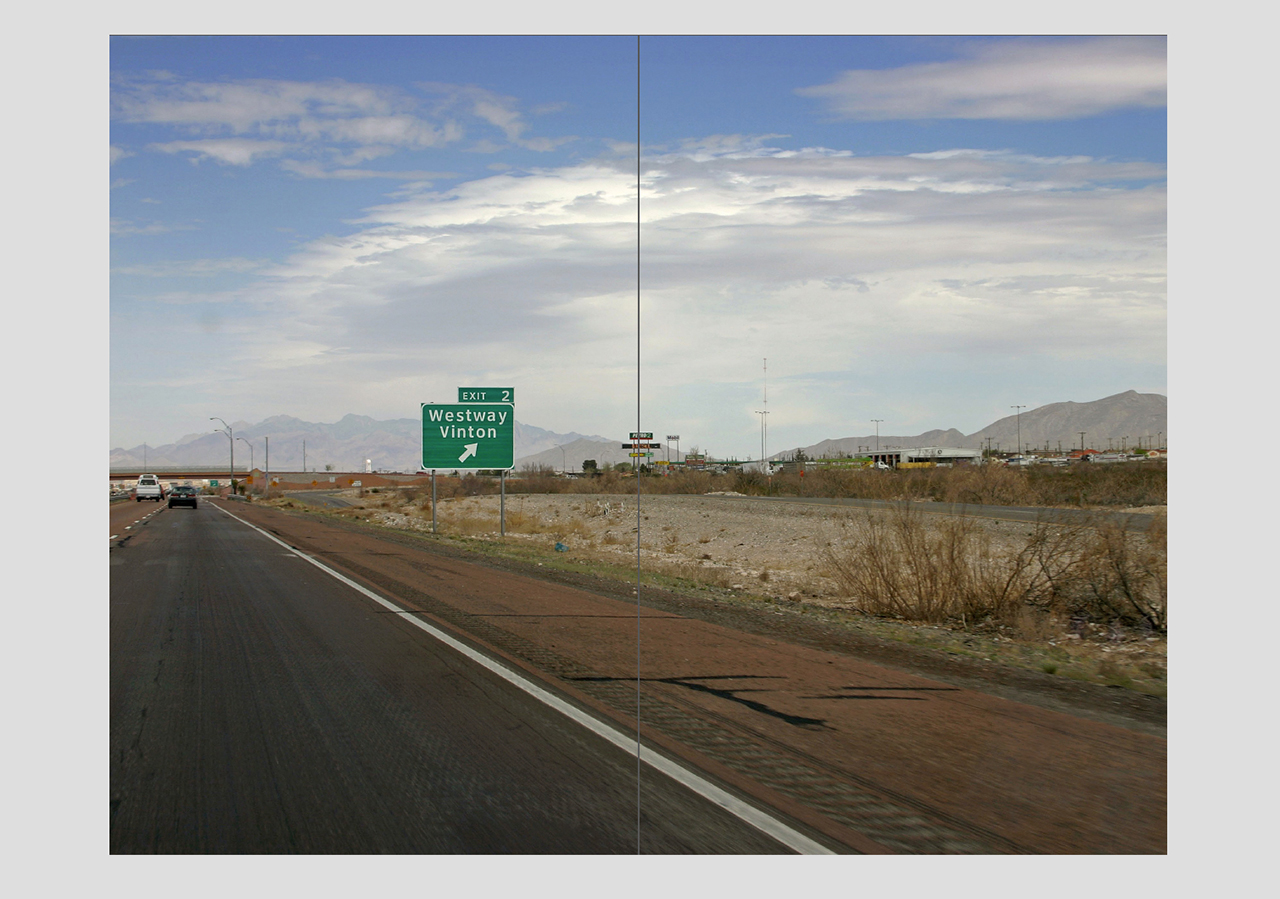

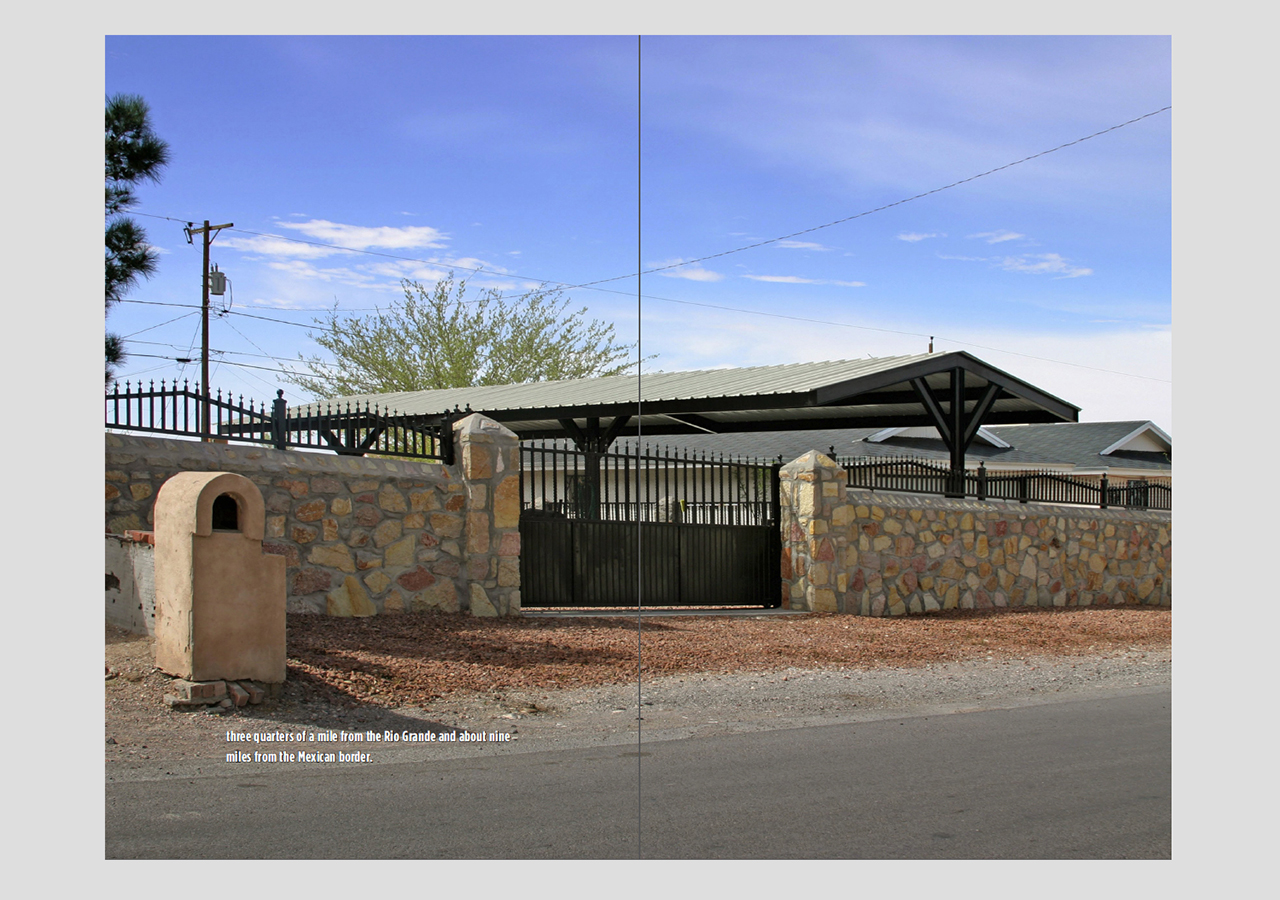

"Years ago, when I lived in New Mexico for a period of time, there was a small blue-collar town named Westway only a few miles away, across the state border in Texas. Westway is a predominantly Mexican-American residential settlement of 4,200 that grew up organically over the last twenty years around a large commercial truck-stop along I-10. It lies only about three quarters of a mile from the Rio Grande and about nine miles from the Mexican border.

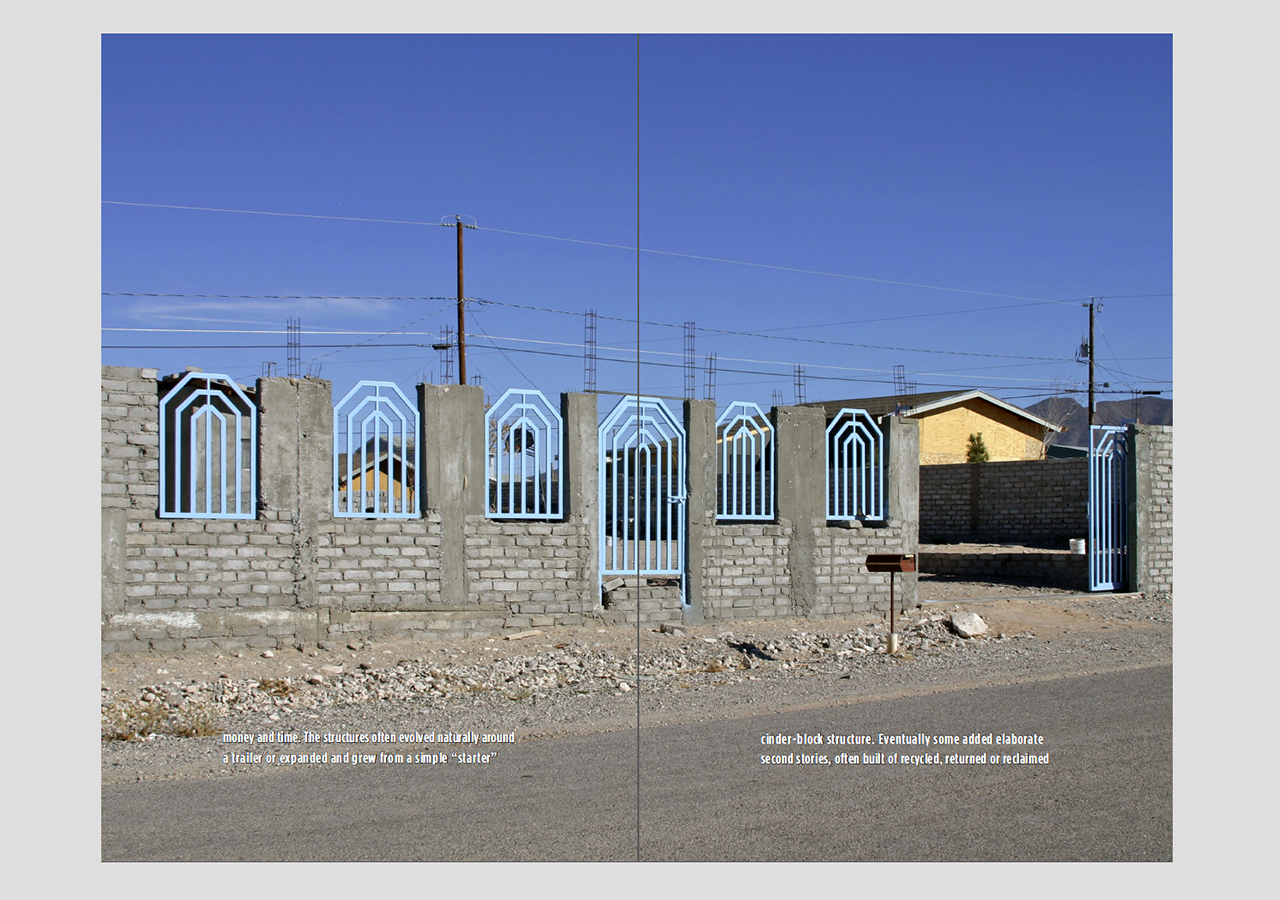

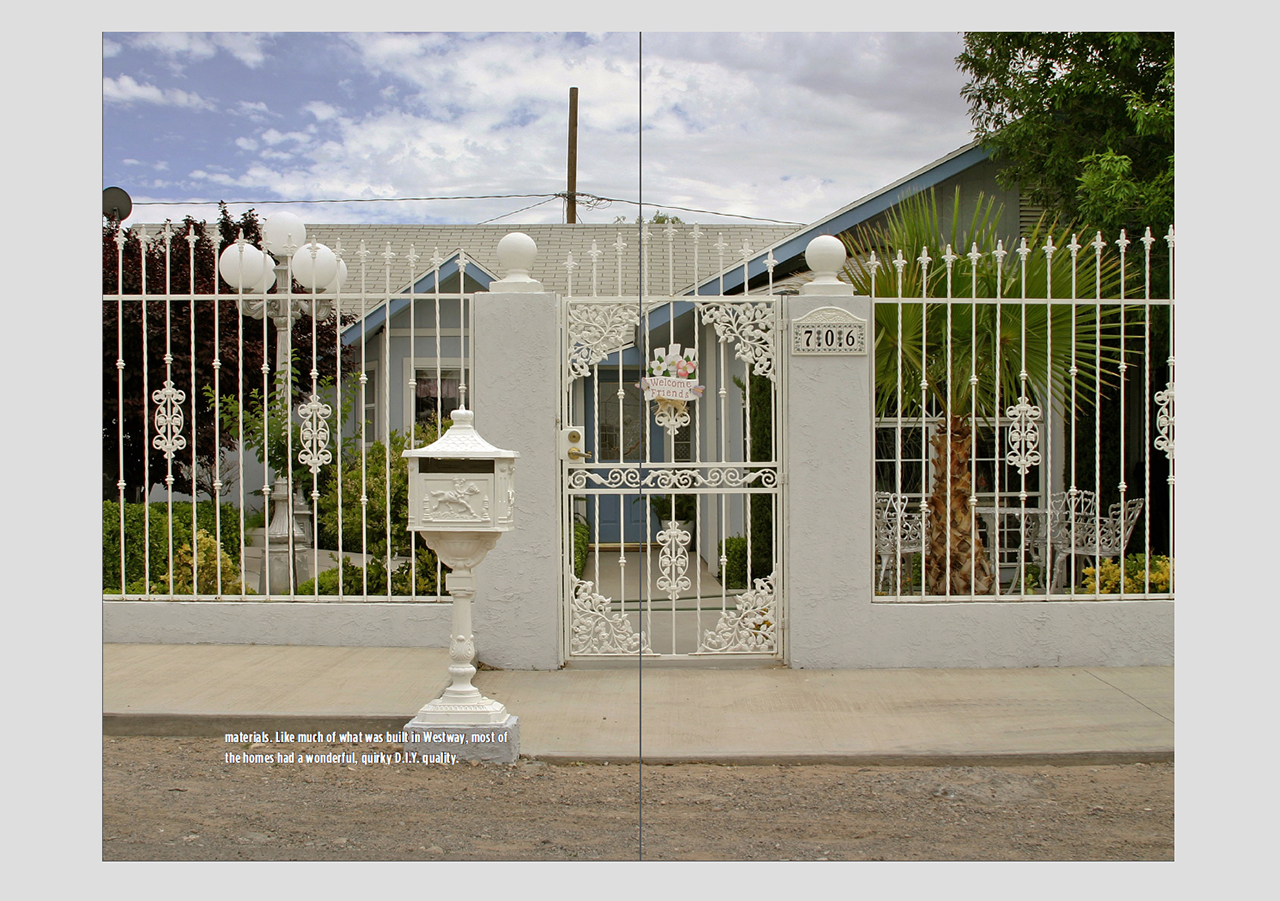

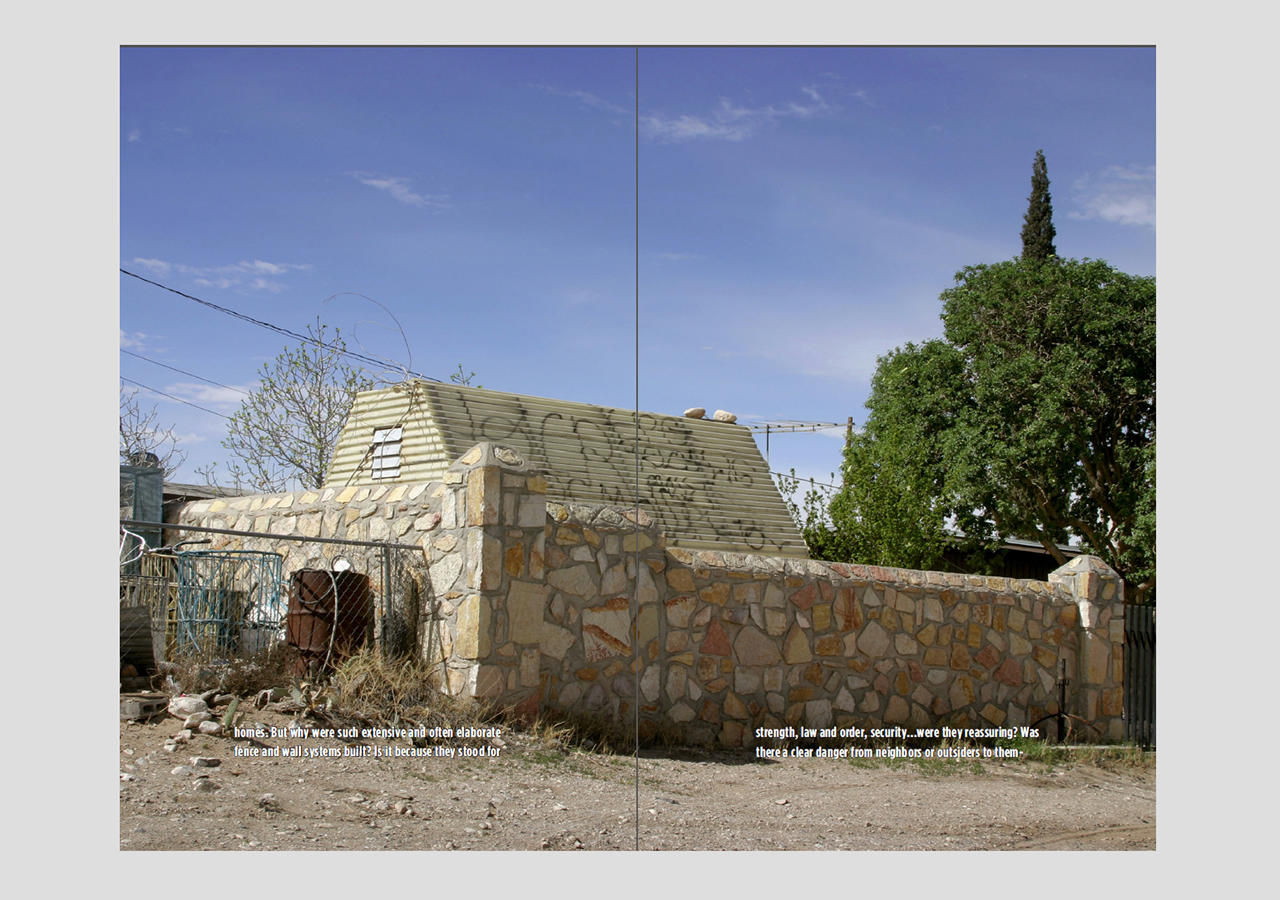

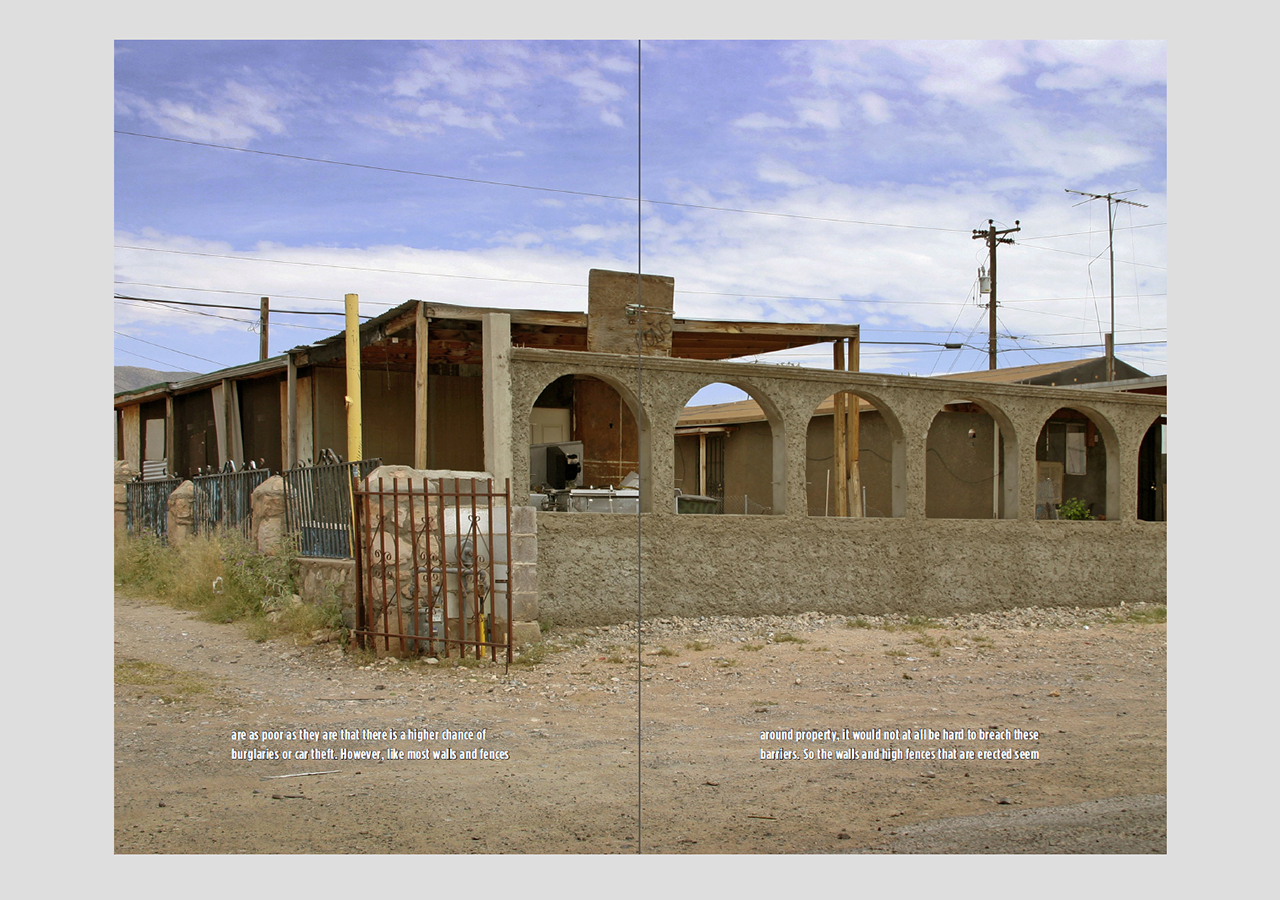

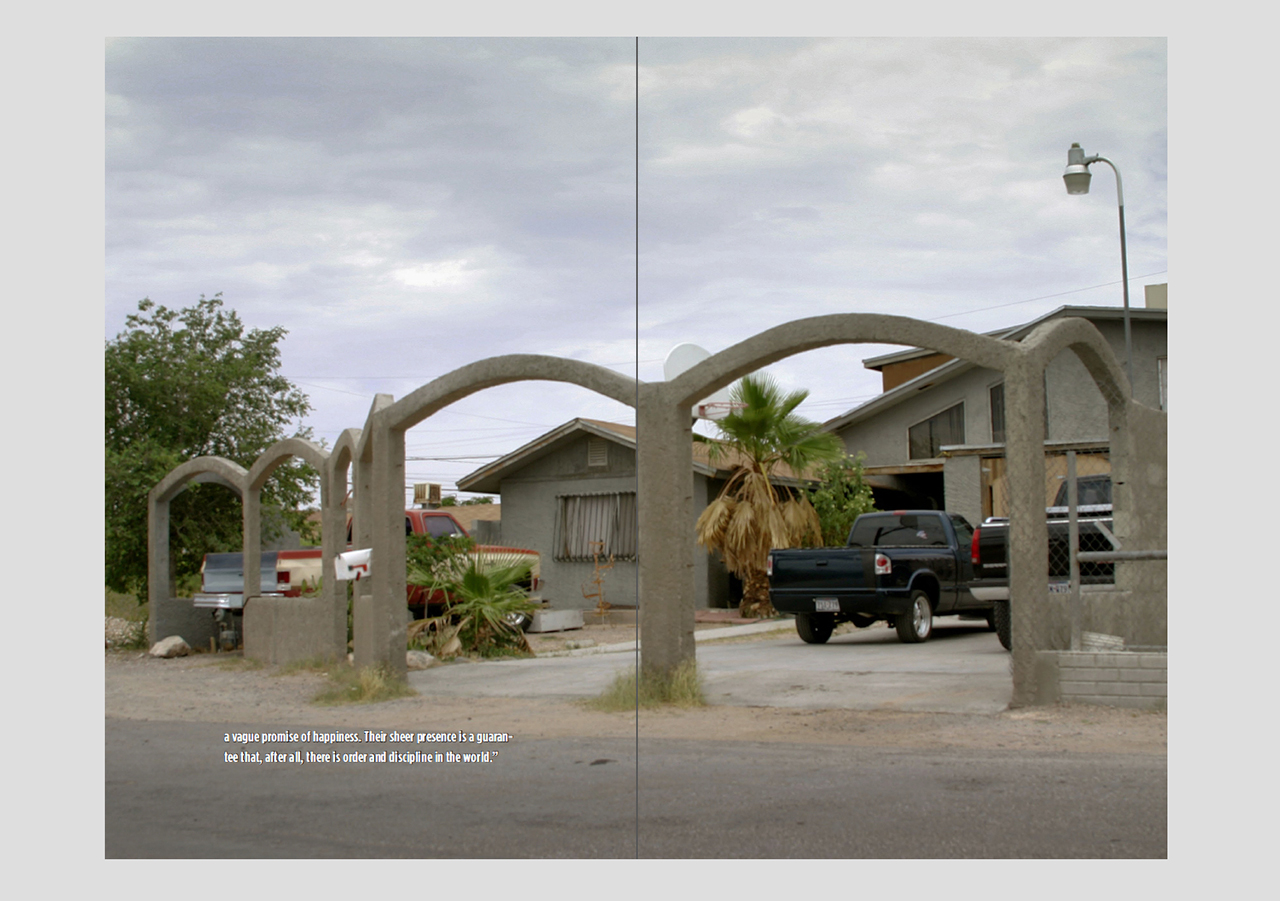

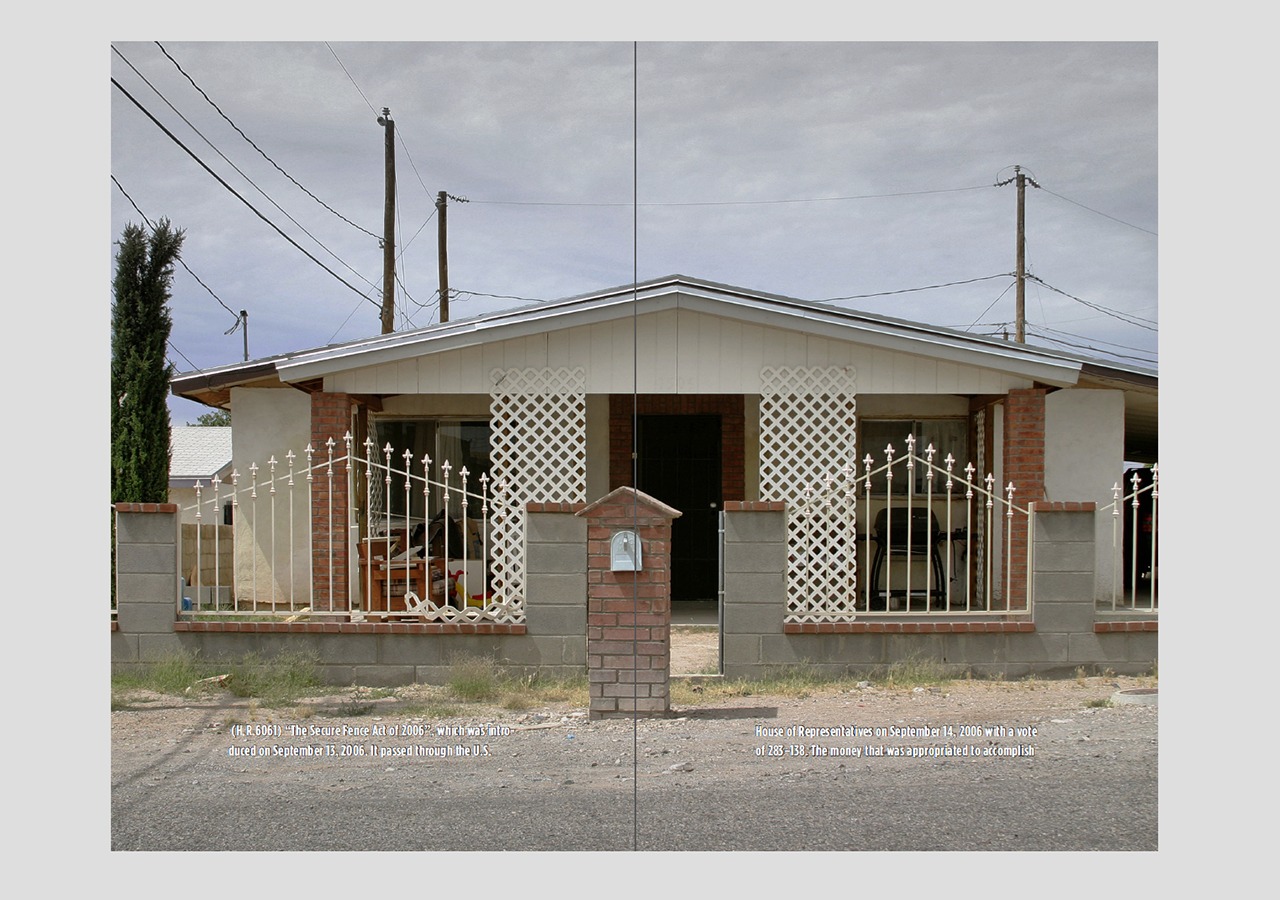

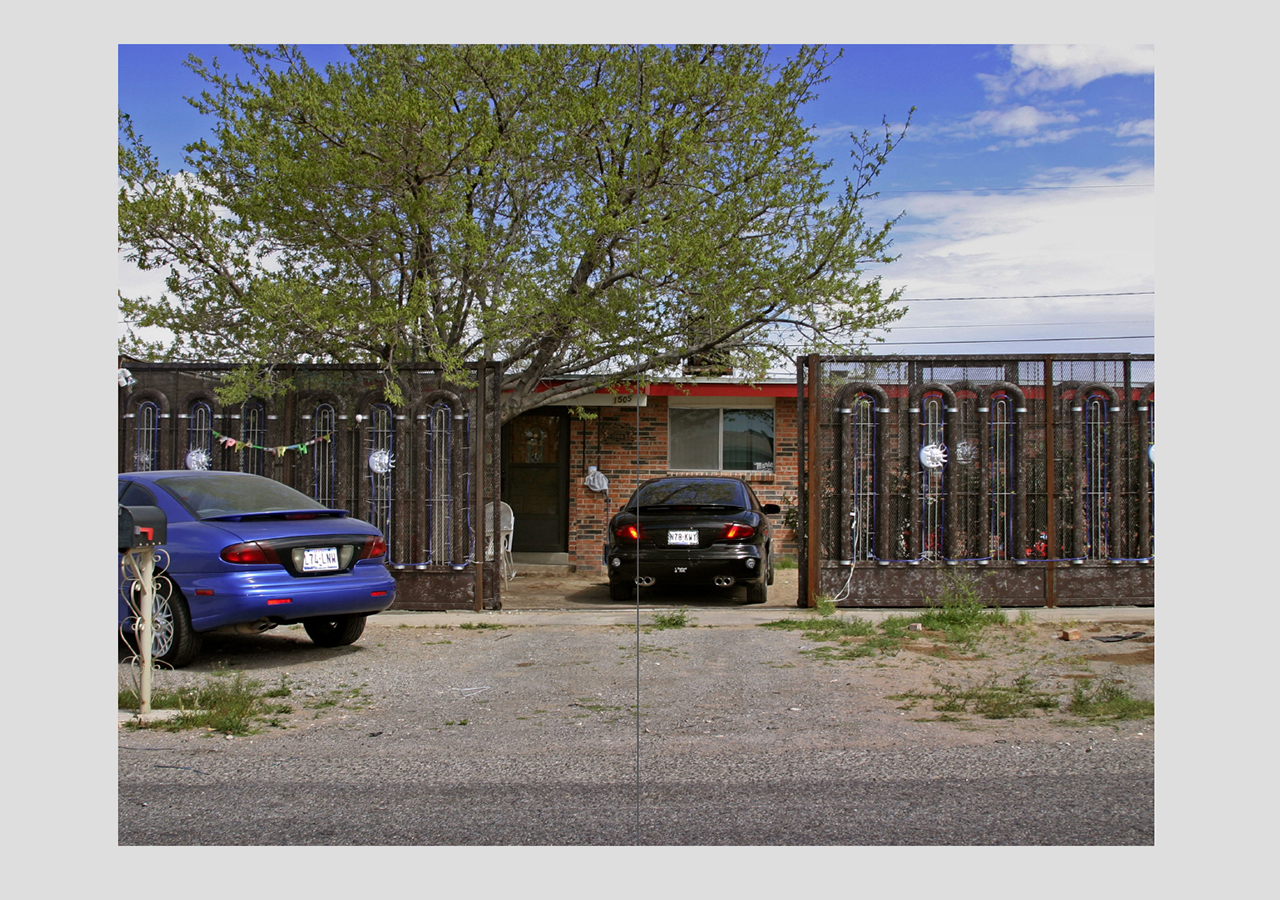

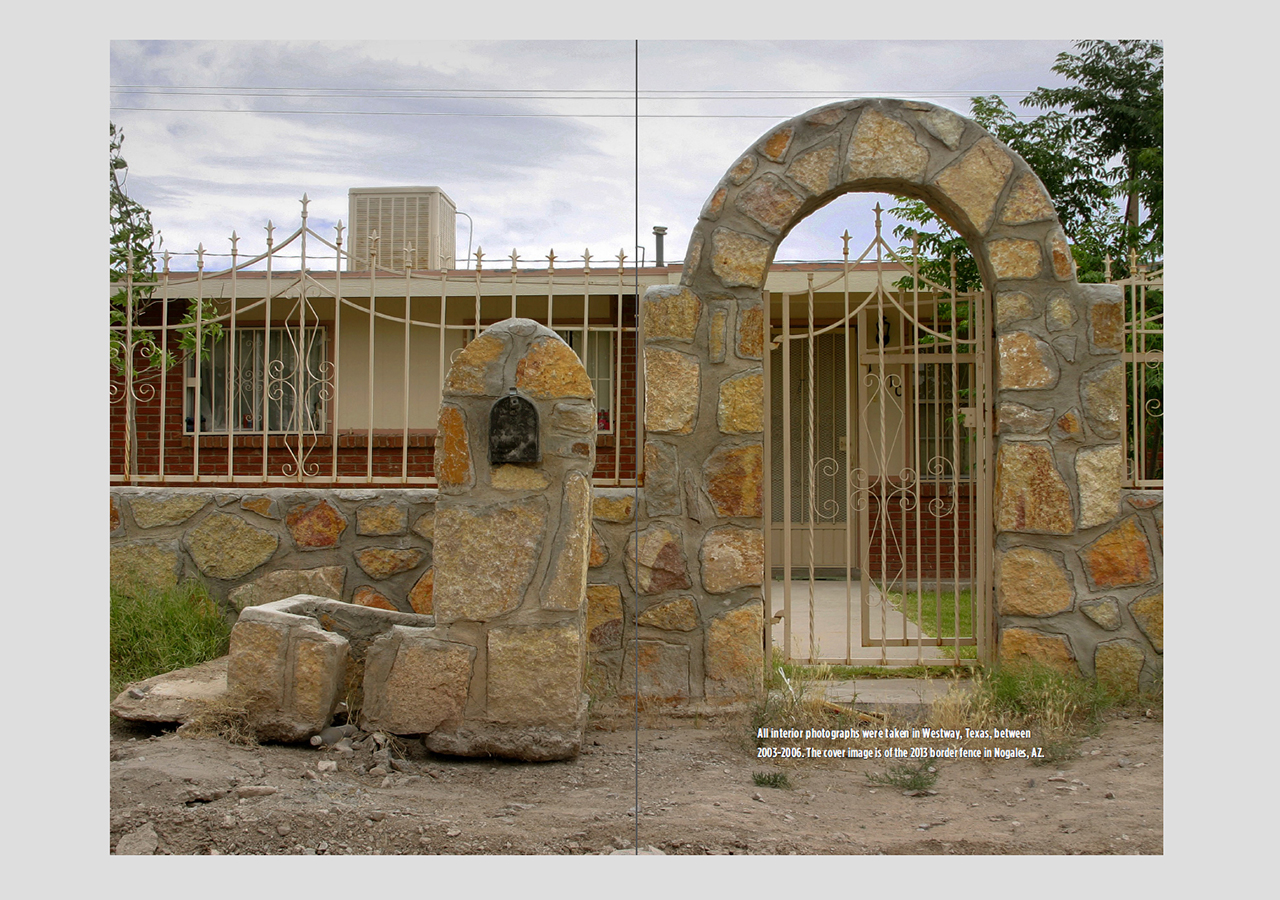

Westway fascinated me. The houses there were almost always owner-built and added onto slowly as the residents had money and time. The structures often grew naturally around a trailer or expanded and grew from a simple “starter” cinder-block structure. Eventually some added elaborate second stories, often built of recycled, returned or reclaimed materials. Like everything built in Westway, the homes had a wonderful, quirky, D.I.Y. quality.

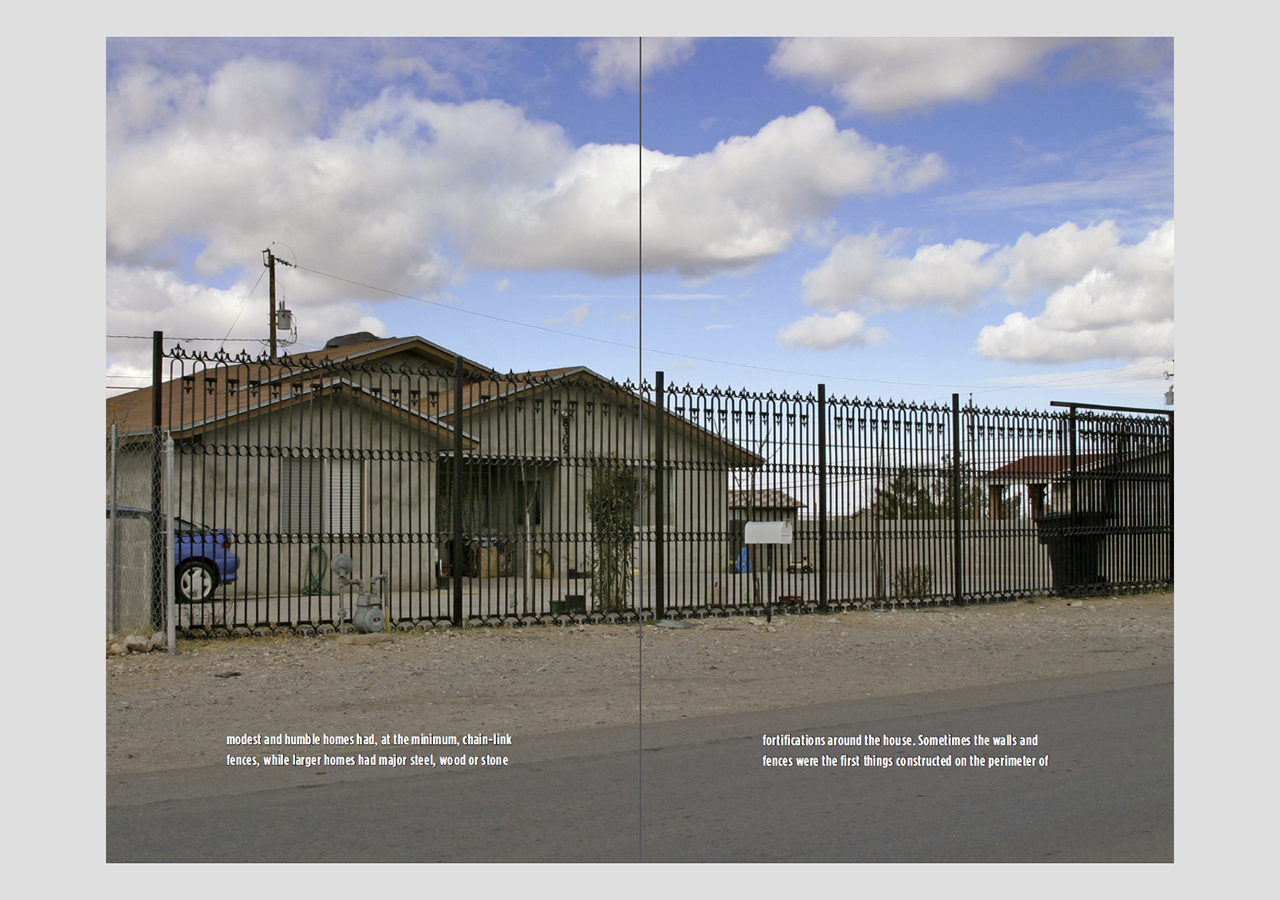

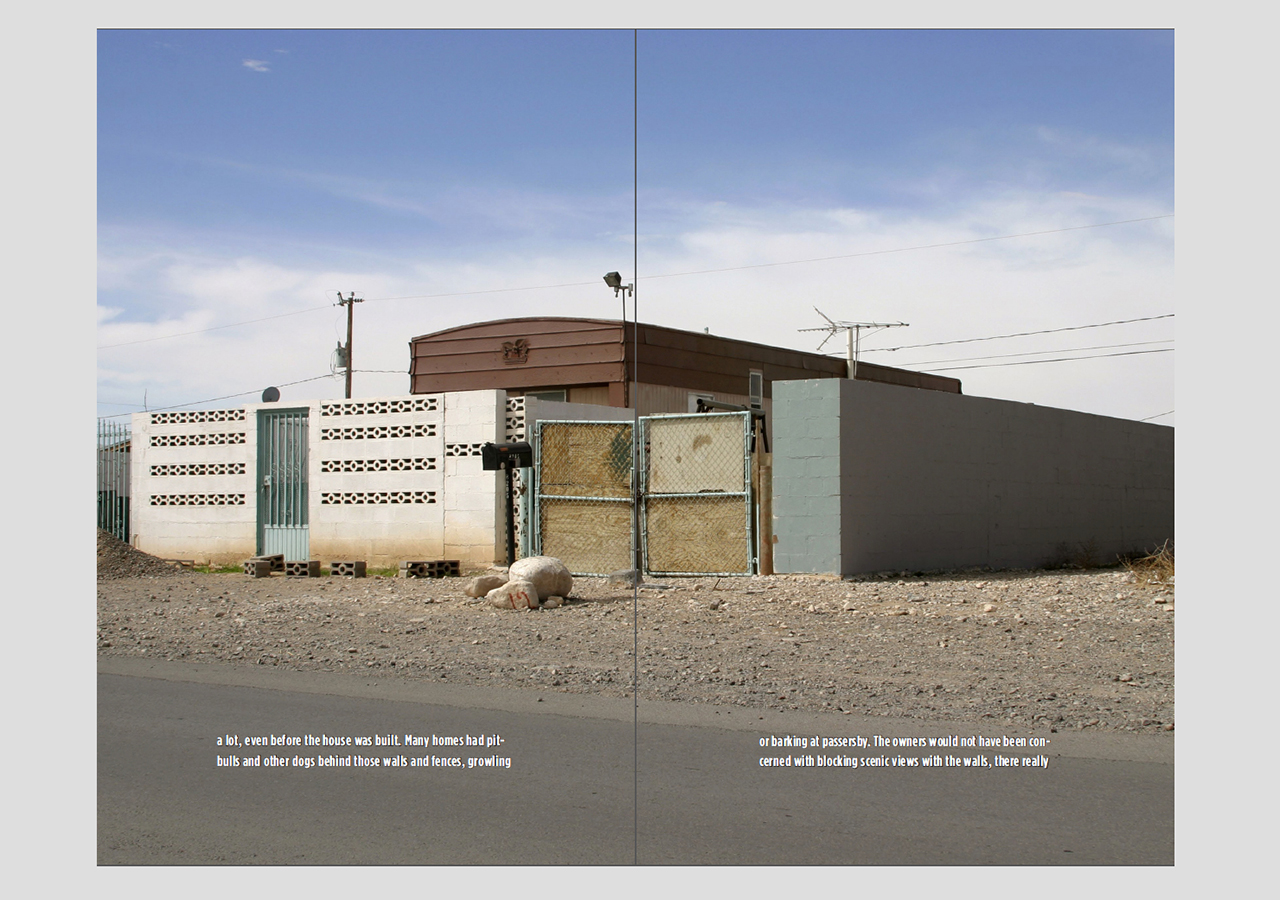

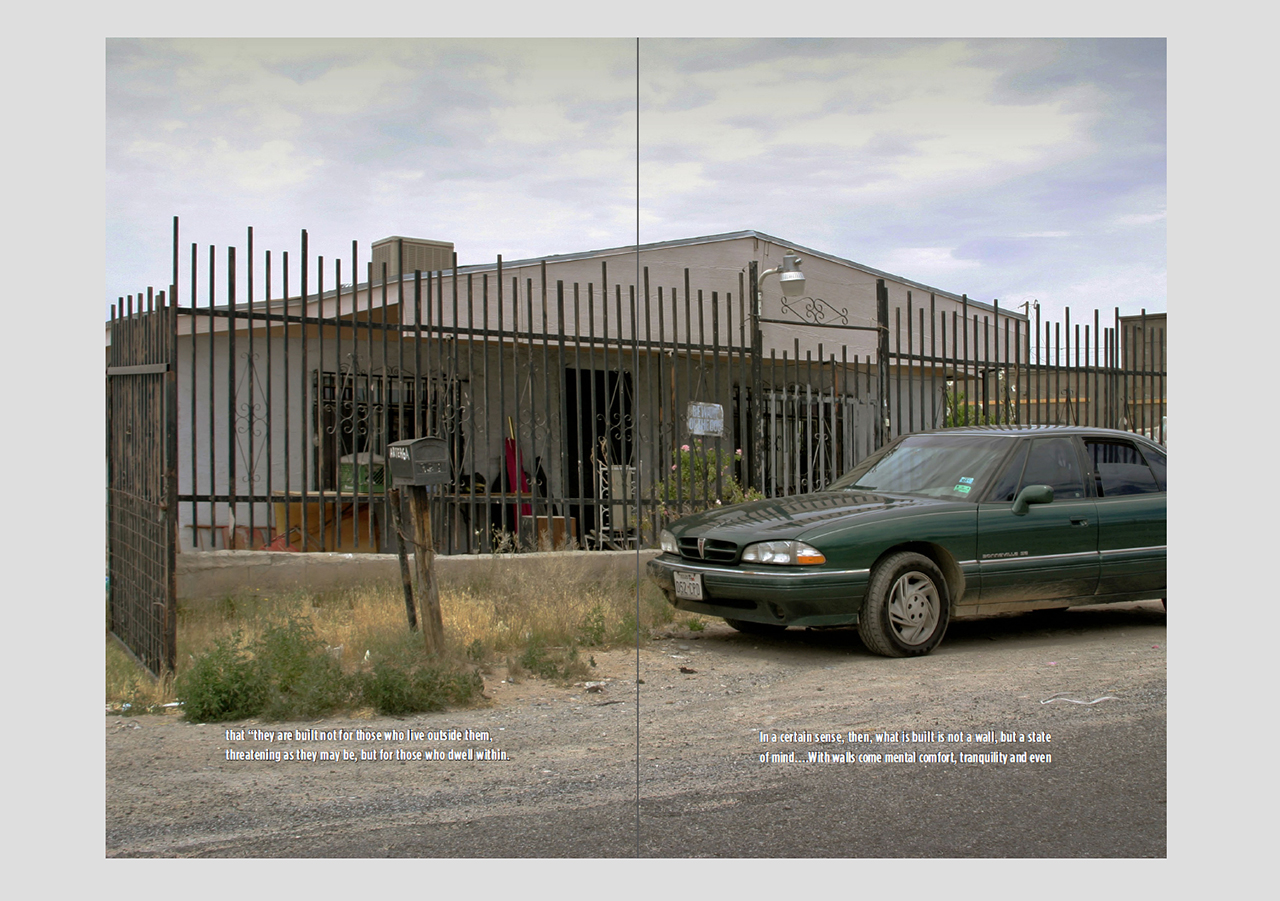

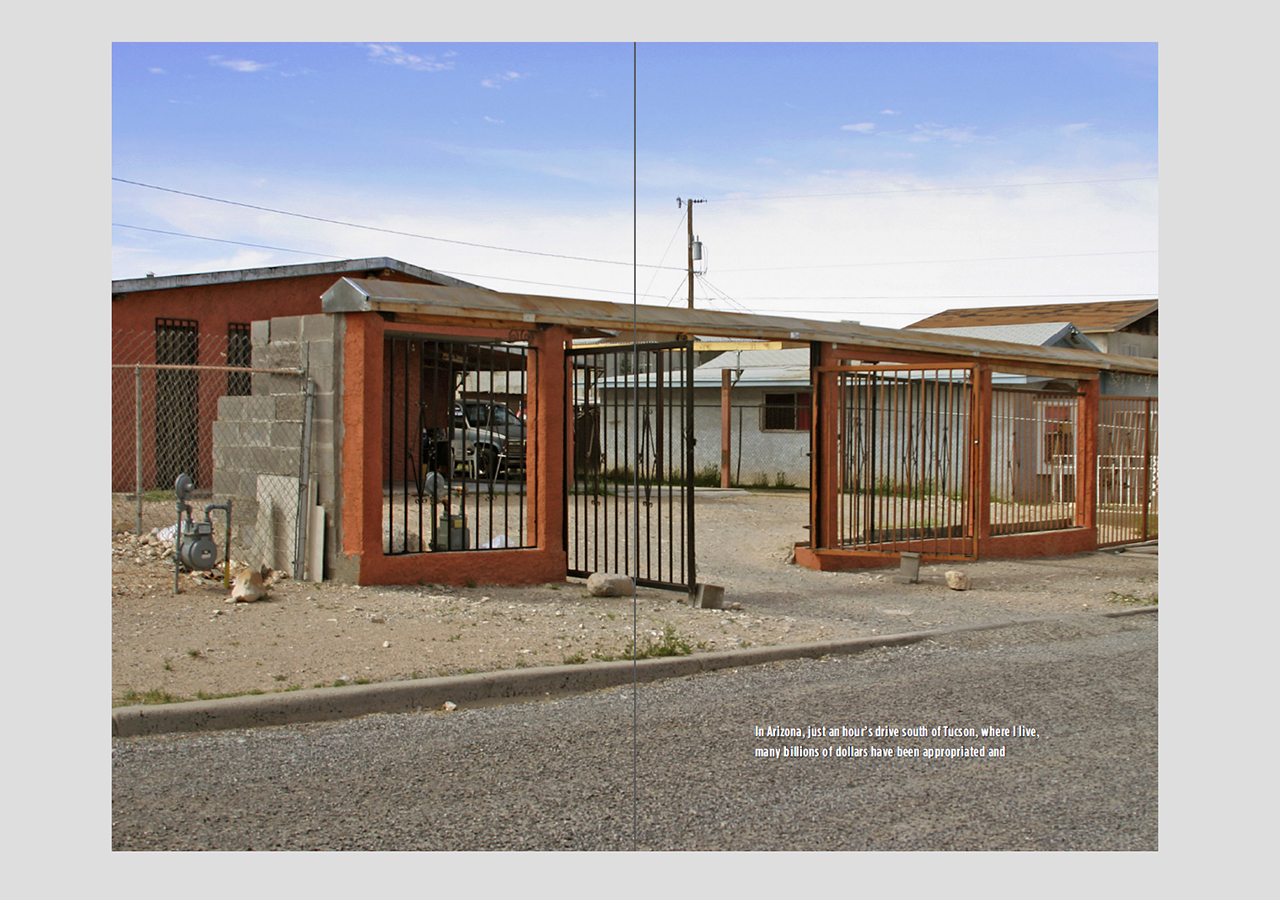

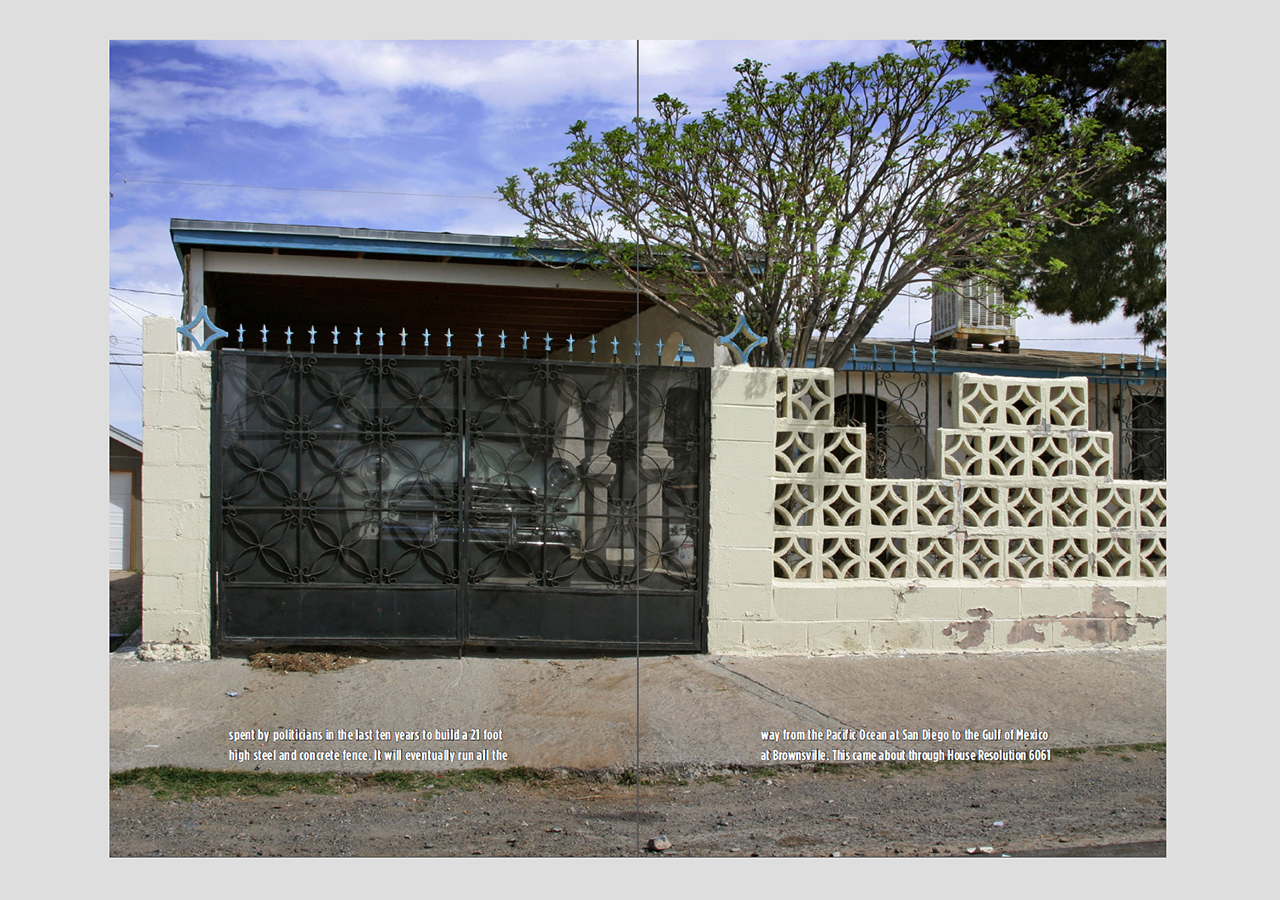

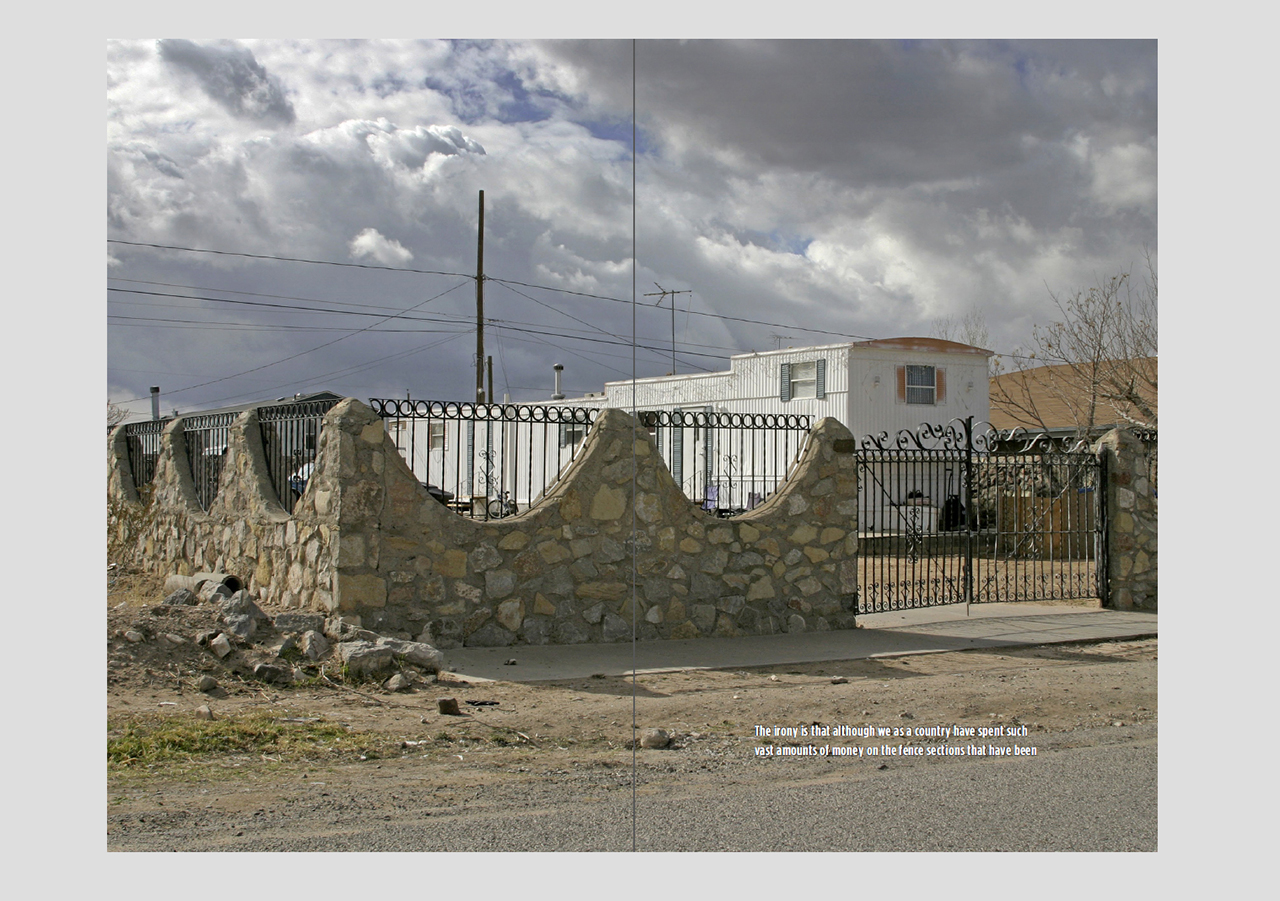

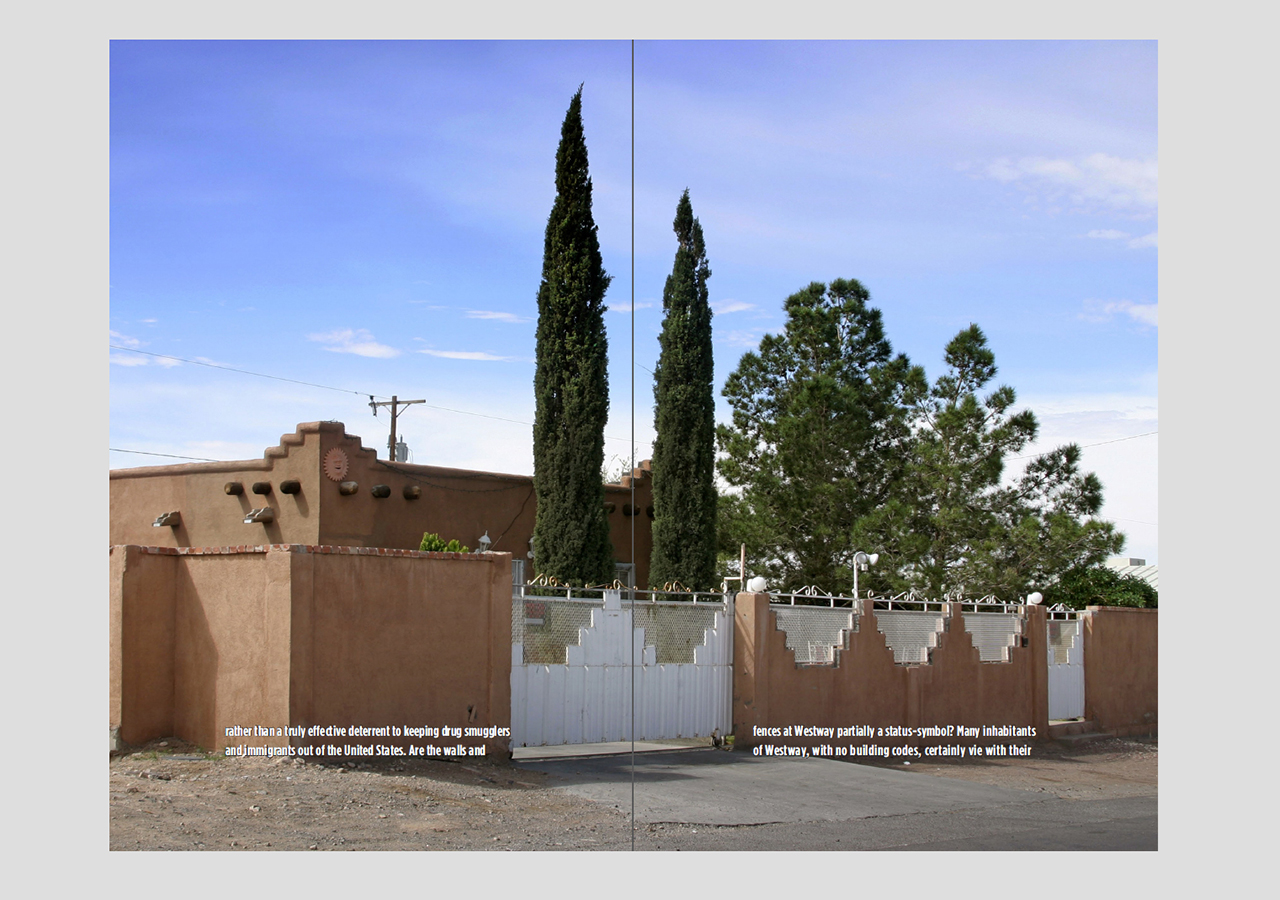

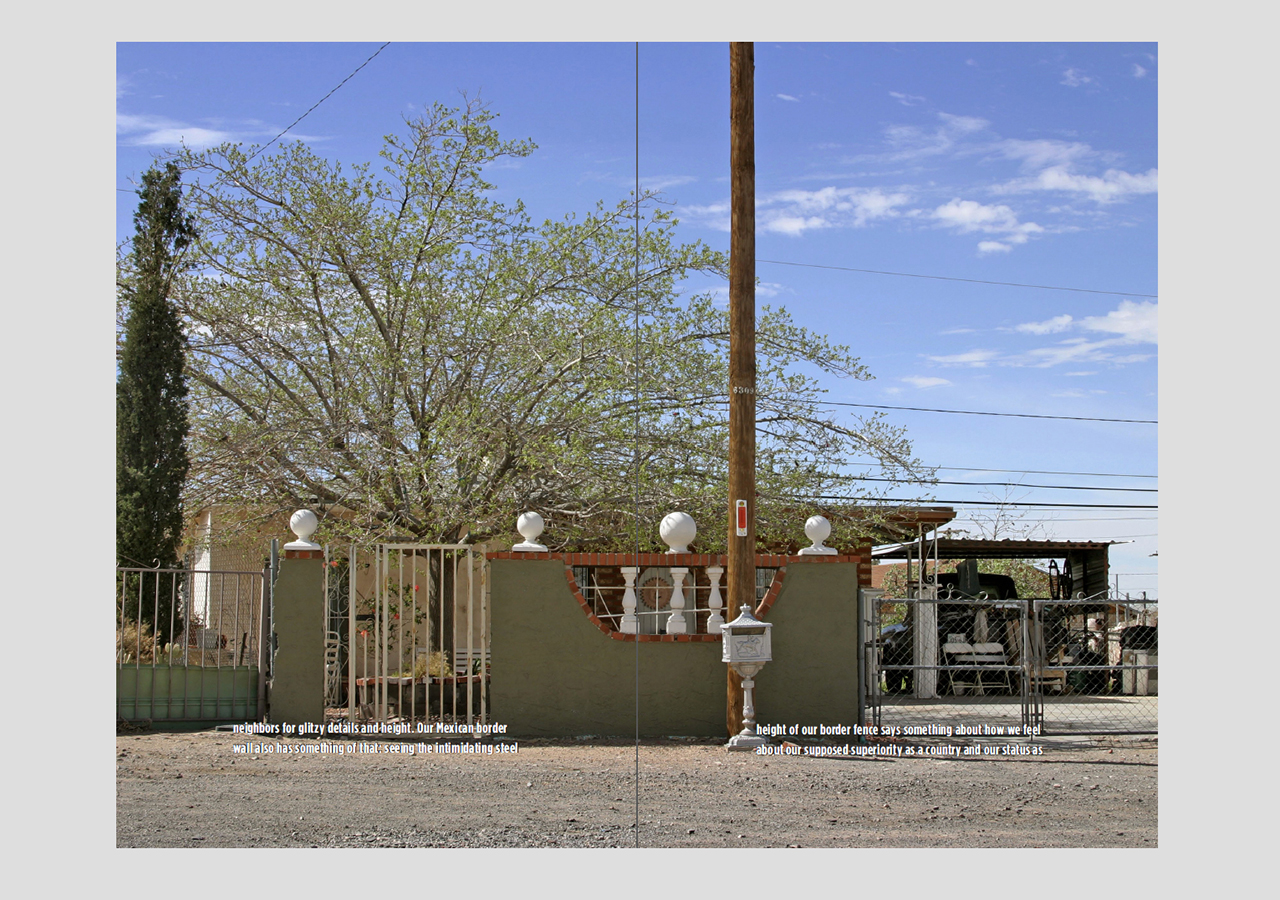

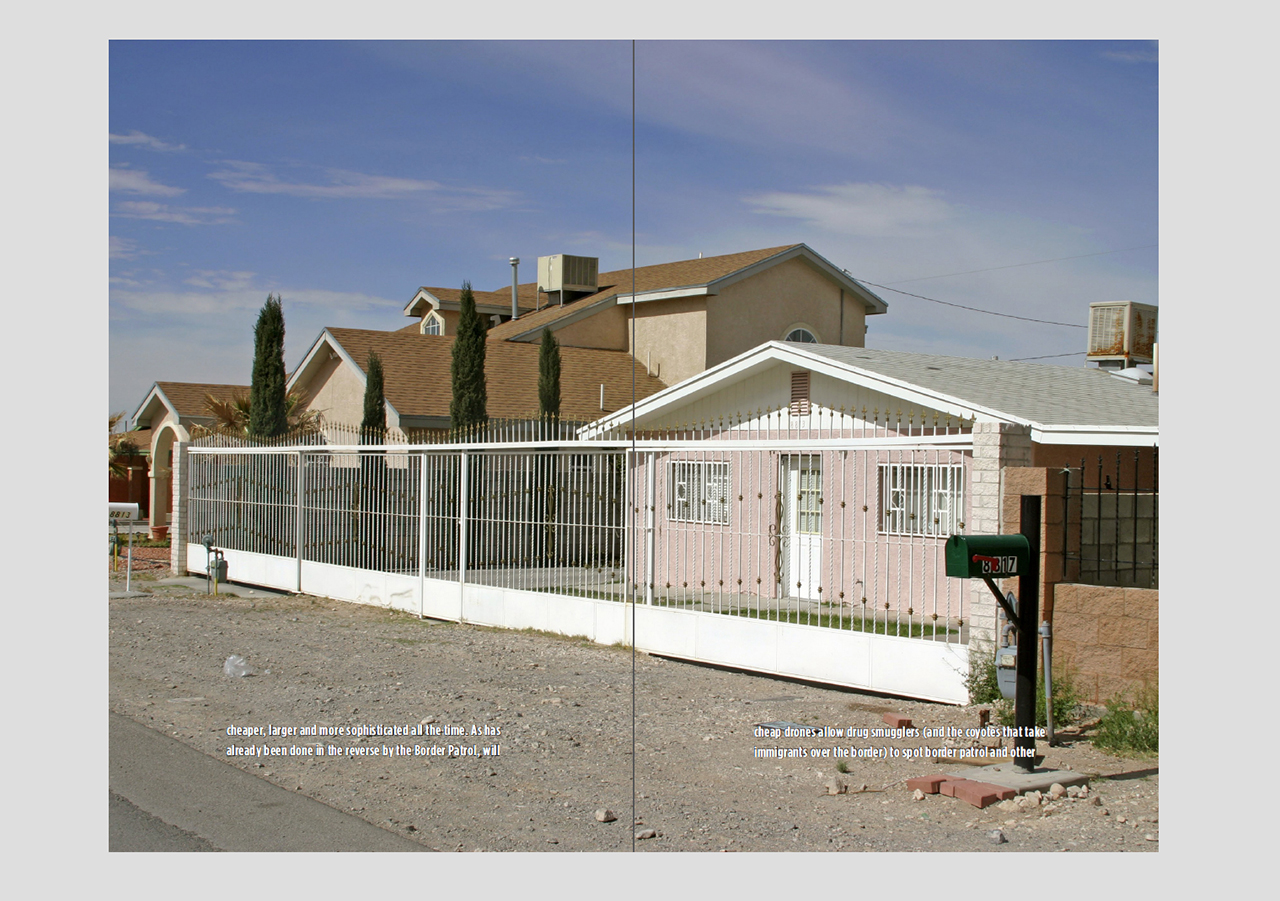

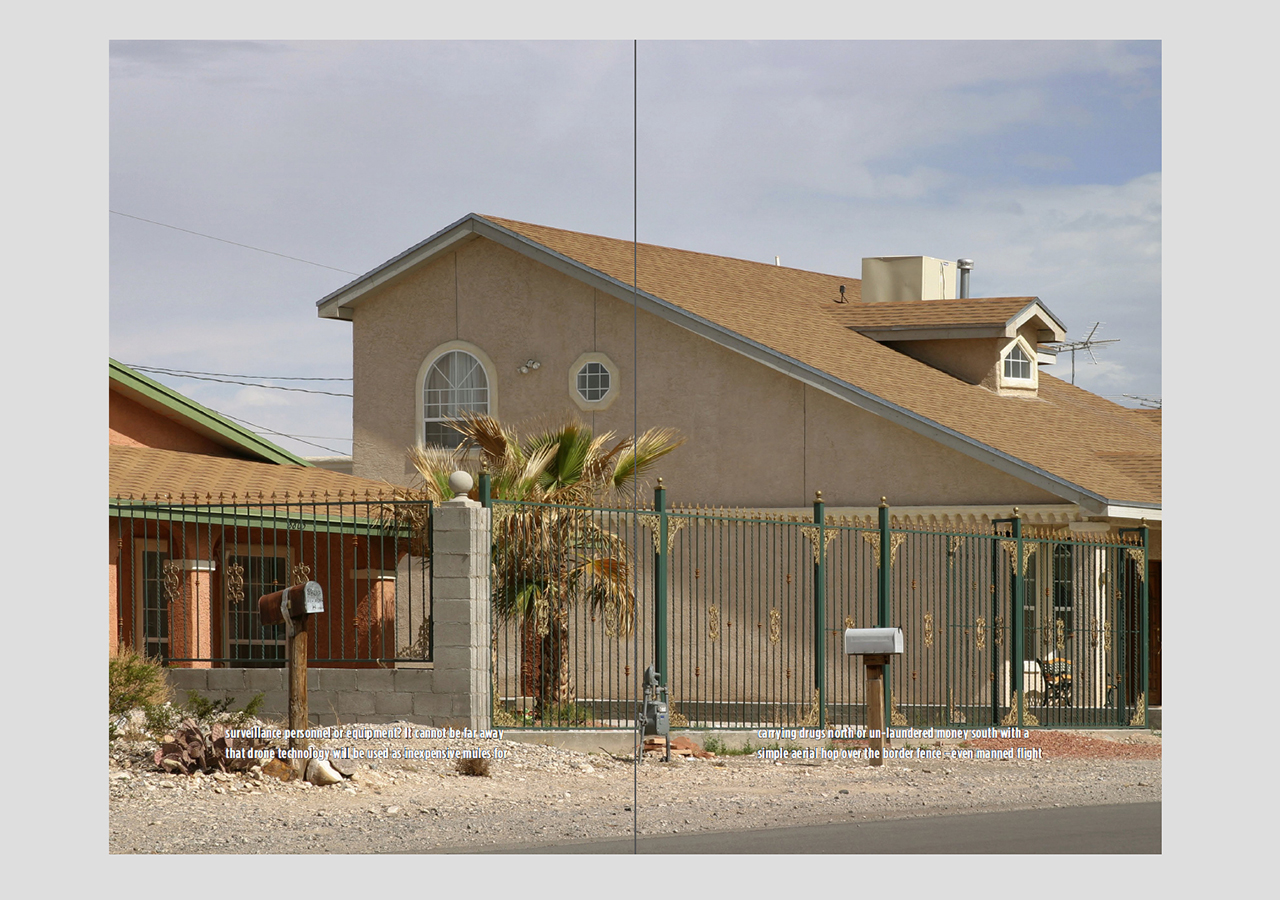

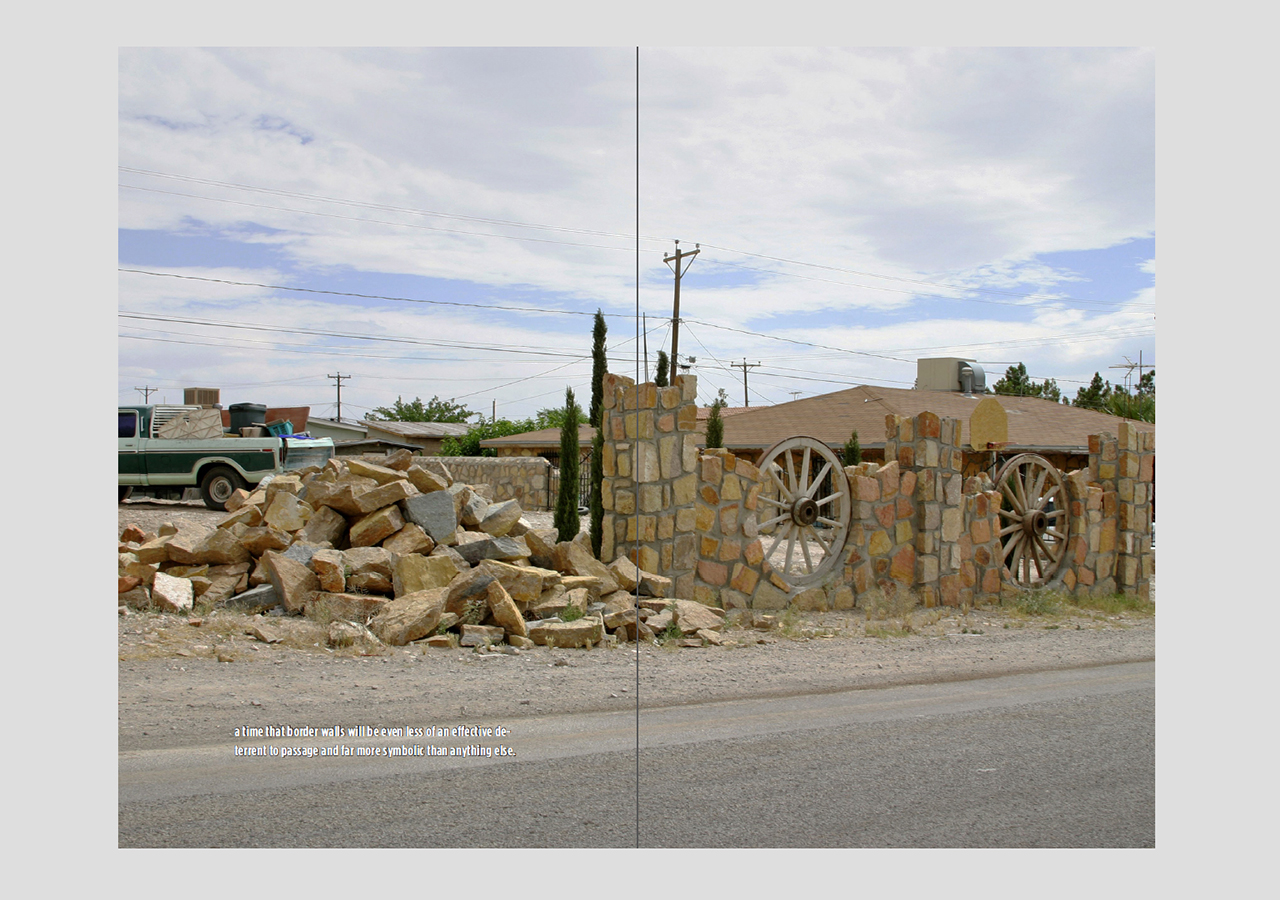

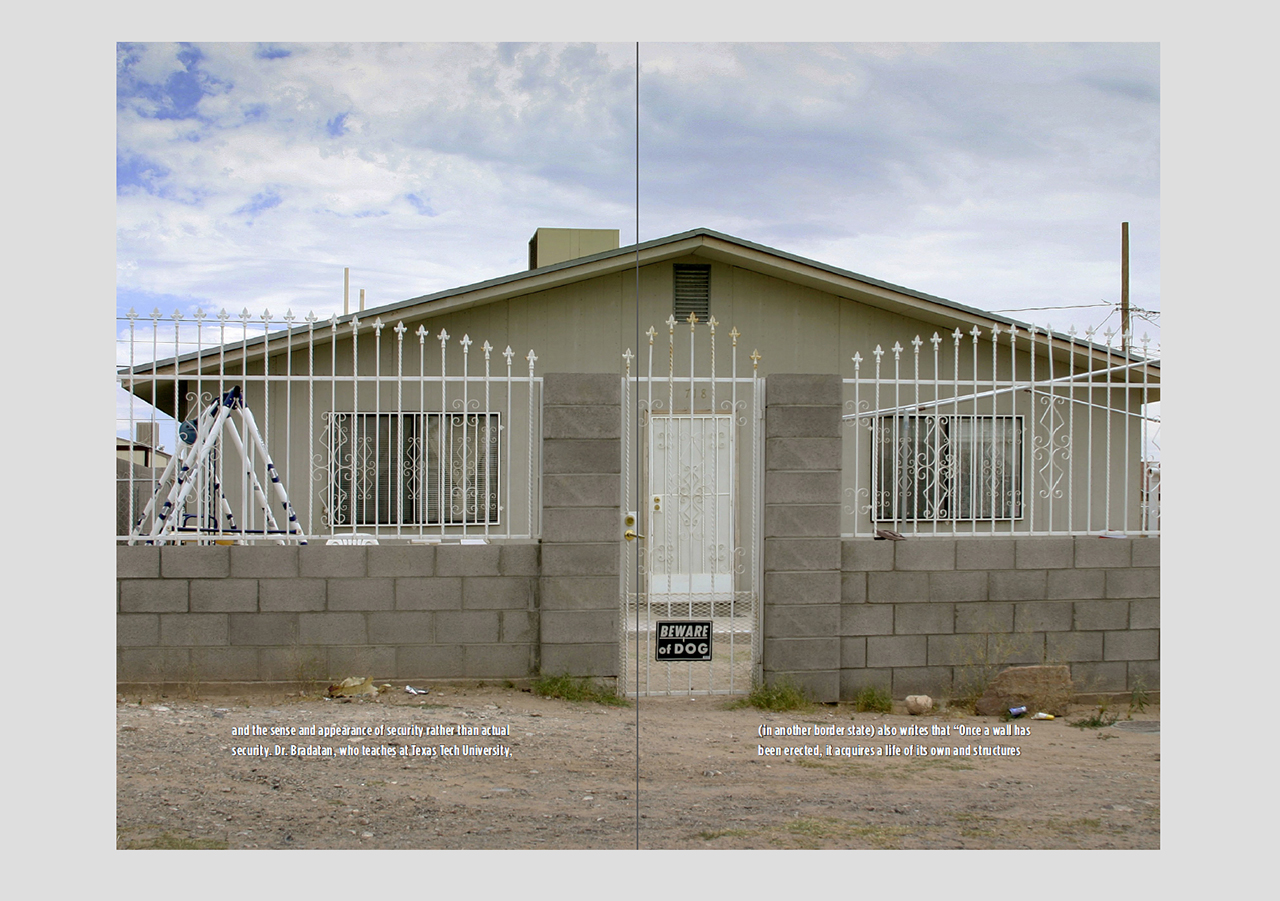

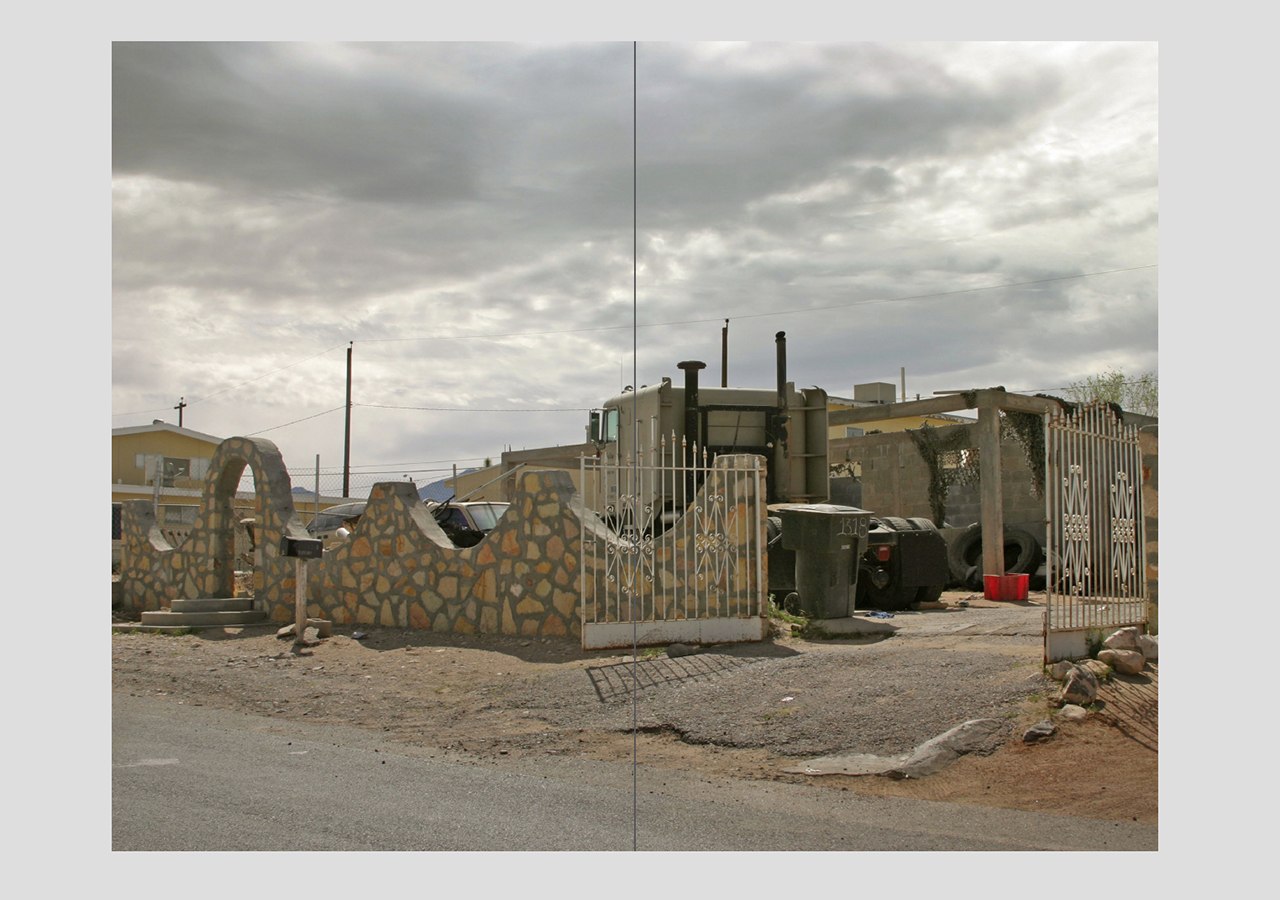

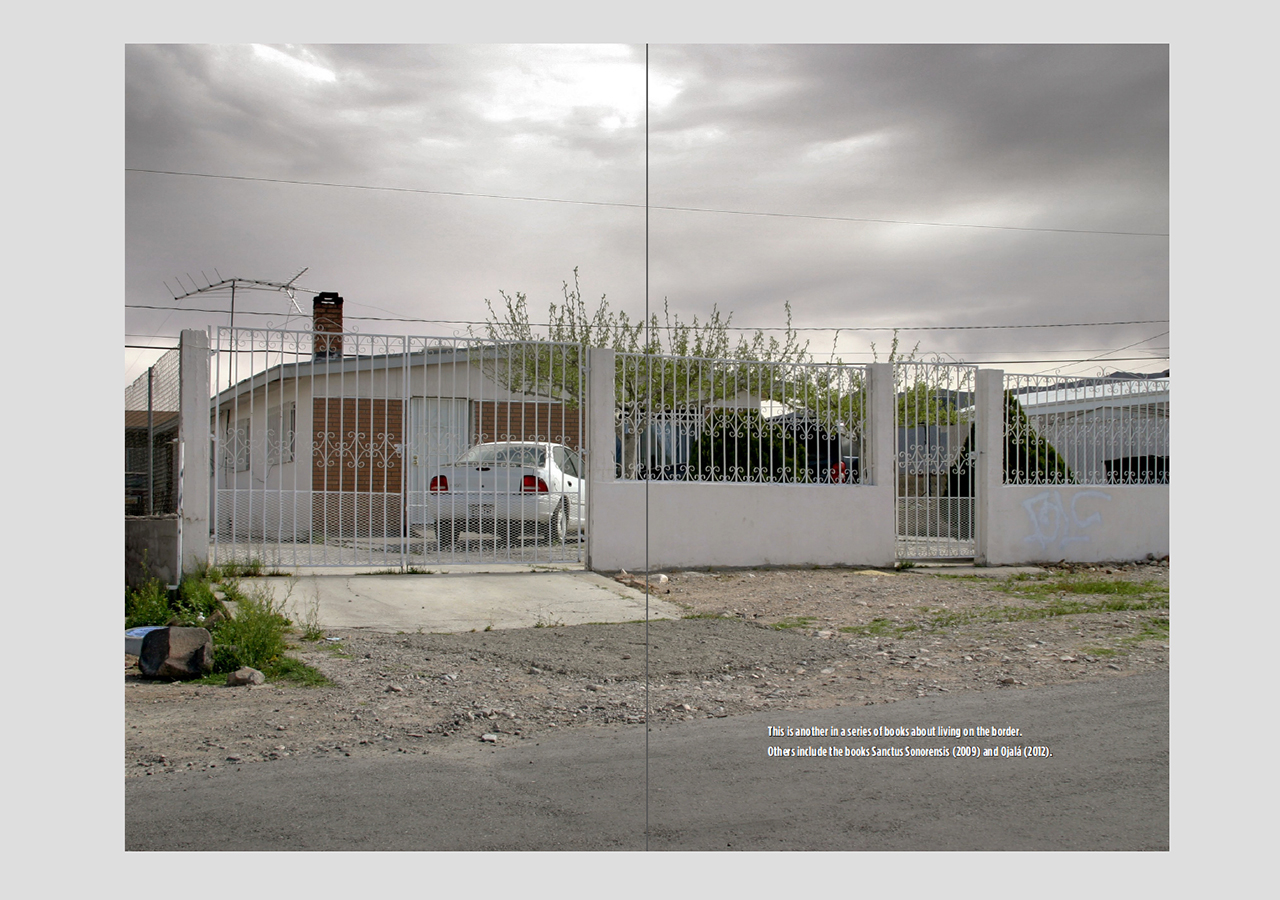

One thing that was common to all of the houses were the significant surrounding walls and fences. Even the most modest and humble homes had at the minimum chain-link fences, while larger homes had major steel, wood or stone fortifications around the house. Sometimes the walls and fences were the first things constructed on the perimeter of a lot, even before the house was built. Many homes had pit-bulls and other dogs behind those walls and fences, growling or barking at passersby. The owners would not be concerned with blocking scenic views with the walls, there really isn’t much of a view in Westway to block: it’s dusty and dry scrub desert along an interstate highway.

Though these were not wealthy folks (there are almost no paved roads in Westway) they took great pride in their homes. But why were such extensive and often elaborate fence and wall systems built? Is it because they stood for strength, law and order, security…were they reassuring? Was there a clear danger from neighbors or outsiders to themselves and their property? I looked up police blotter reports for the area and there did not seem to be much crime at all, certainly not any more significant violence or theft than in any other nearby community.

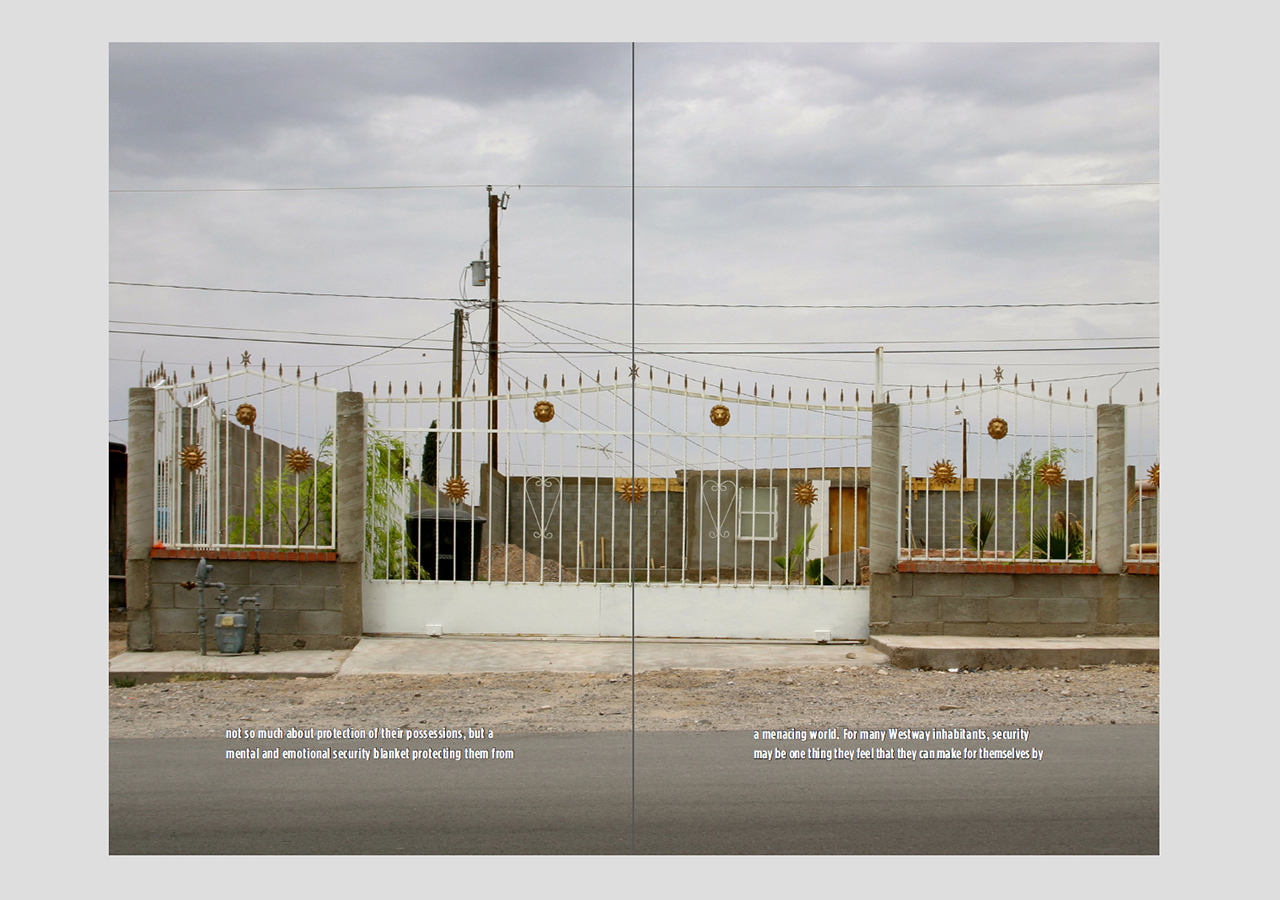

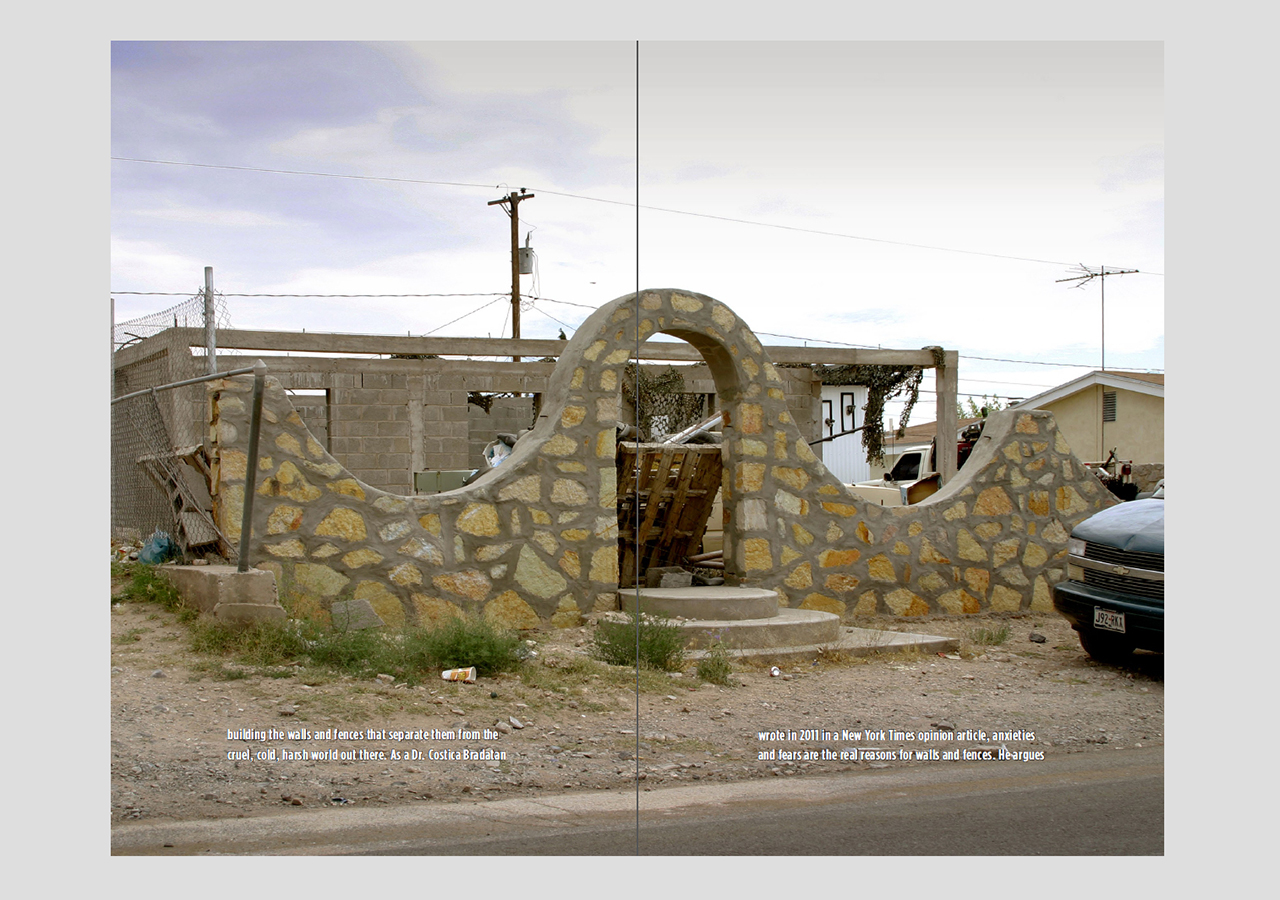

It could be that the lack of a local police force makes them feel insecure, or that they feel that because their neighbors are as poor as they are that there is a higher chance of burglaries or car theft. However, like most walls and fences around property, it would not at all be hard to breach these barriers. So the walls and fences that are erected are really not so much about protection of their possessions, but a mental protection from the harsh world out there. Westway inhabitants are not wealthy, and security may be one thing they feel that they can make for themselves (and own) by building the walls and fences that separate them from the cruel, cold, harsh world out there. As a Dr. Costica Bradatan wrote in 2011 in a New York Times opinion article, anxieties and fears are the real reasons for walls and fences. He argues that “they are built not for those who live outside them, threatening as they may be, but for those who dwell within. In a certain sense, then, what is built is not a wall, but a state of mind….With walls come mental comfort, tranquility and even a vague promise of happiness. Their sheer presence is a guarantee that, after all, there is order and discipline in the world.”

So, does Robert Frost’s homey New England proverb, “good fences make good neighbors”, hold true? Is it only to give the builders a certain sense of security? There are those that think a wall, in addition to giving a potentially false sense of real security, is also a provocation…

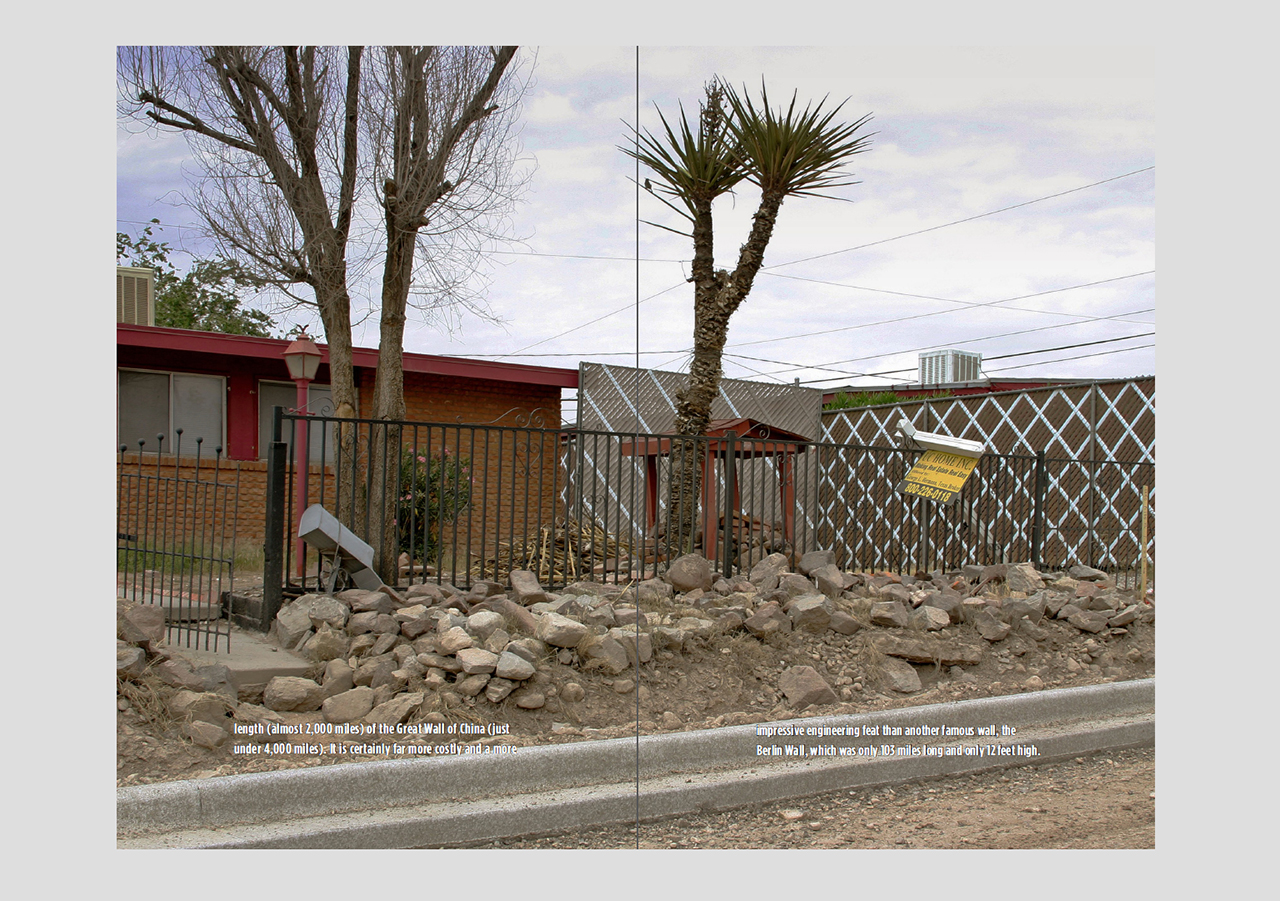

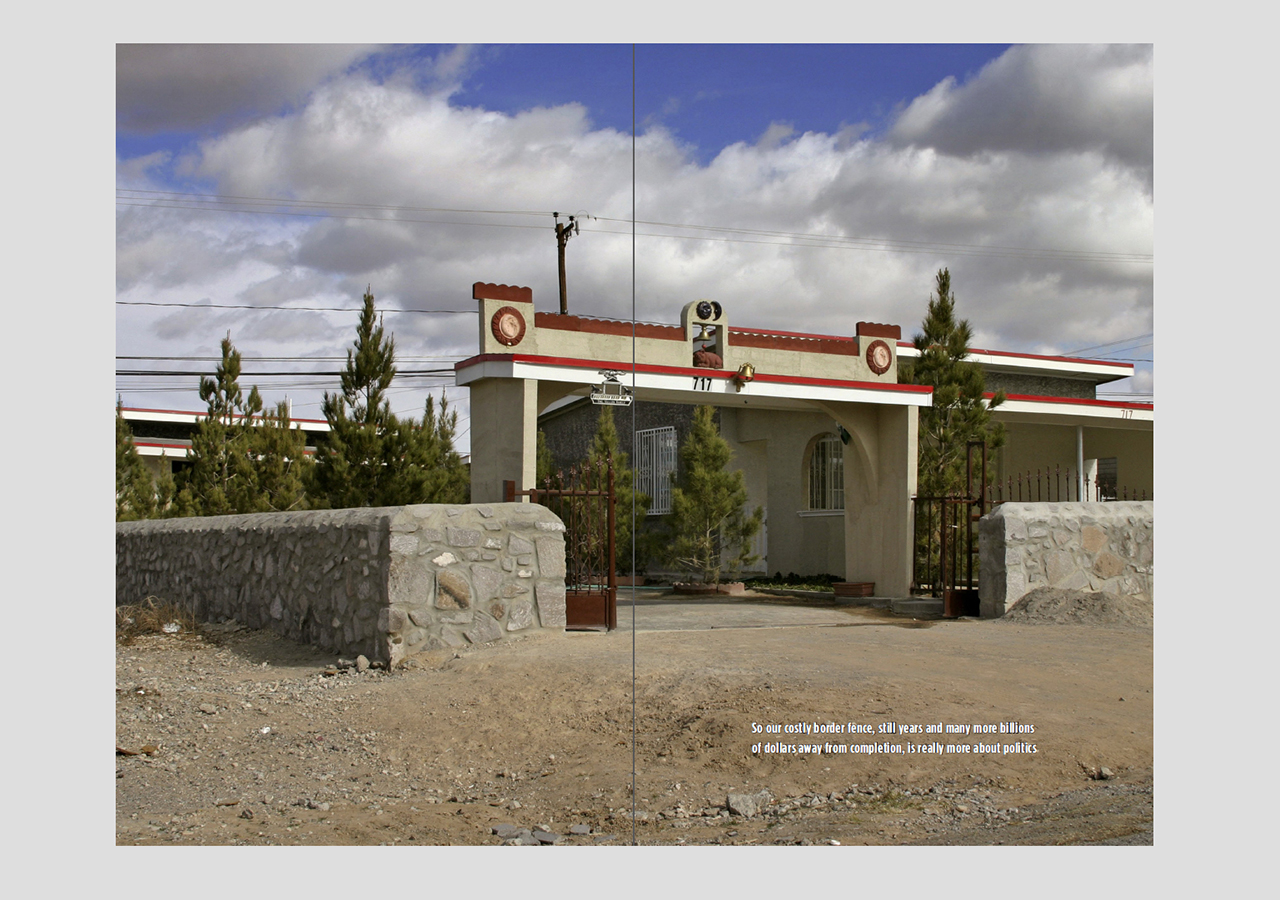

Just an hour’s drive south of where I live now in Tucson, Arizona, many billions of dollars have been appropriated and spent by politicians in the last ten years to build a 21 foot high steel and concrete fence. It will eventually run all the way from the Pacific Ocean at San Diego to the Gulf of Mexico at Brownsville. This came about through House Resolution 6061 (H.R.6061) “The Secure Fence Act of 2006”, which was introduced on September 13, 2006. It passed through the U.S House of Representatives on September 14, 2006 with a vote of 283–138. The money that was appropriated to accomplish this fence has been depleted and the State of Arizona has a voluntary donation program for citizens to contribute to a pool that would go towards helping with the costs of completing this enormous fence. If completed it would be about half the length (almost 2,000 miles) of the Great Wall of China (just under 4,000 miles). It is certainly far more costly and a more impressive engineering feat than another famous wall, the Berlin Wall, which was only 103 miles long and only 12 feet high.

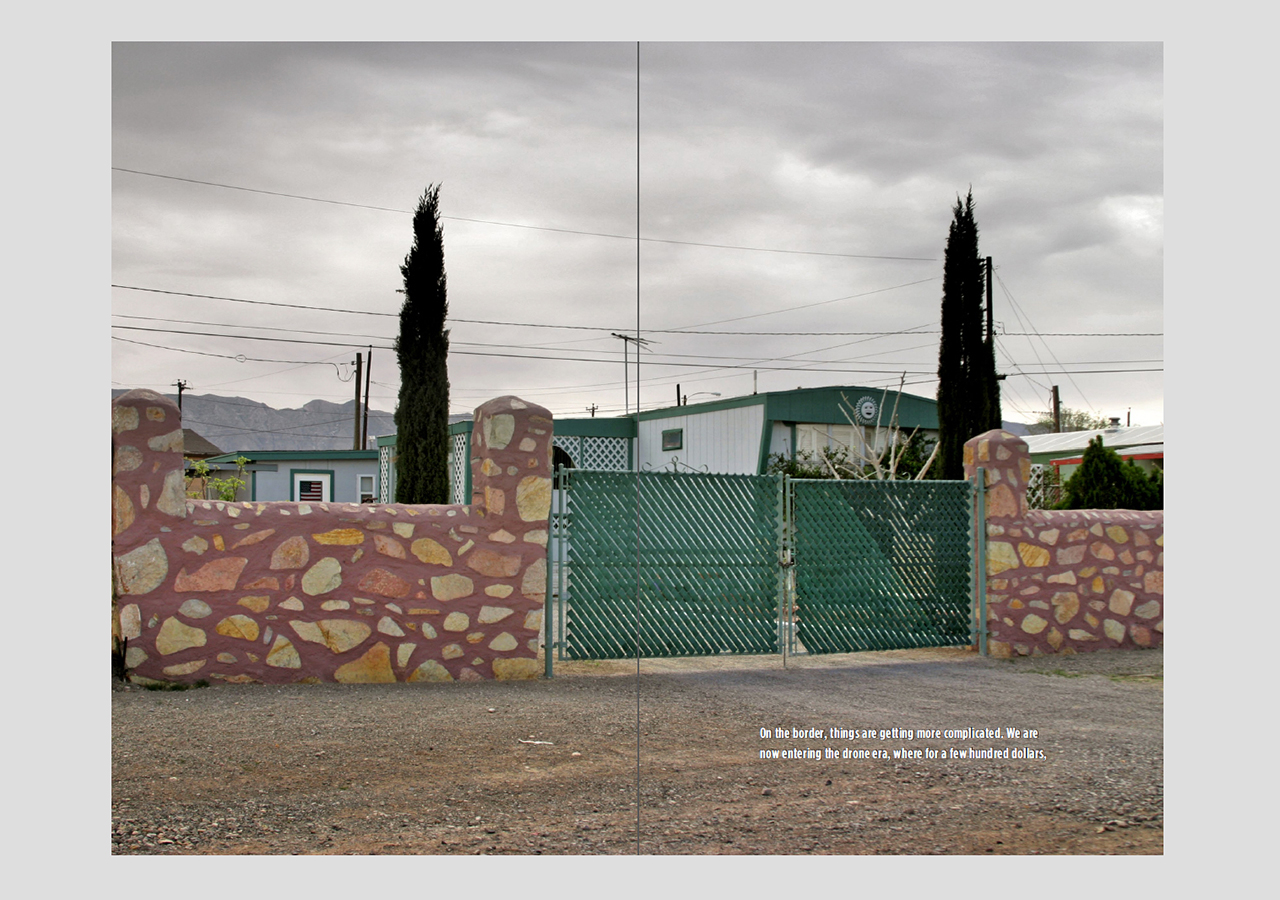

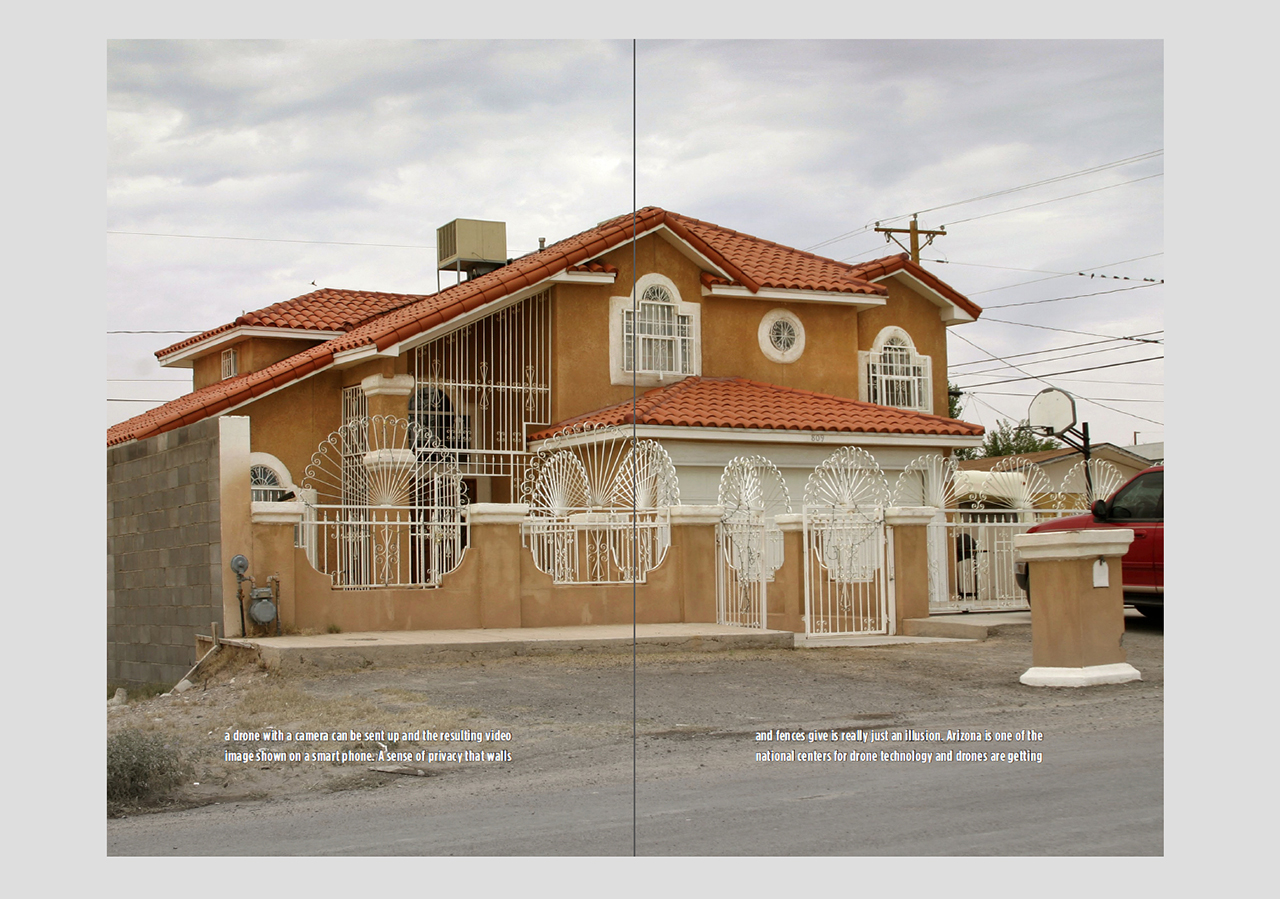

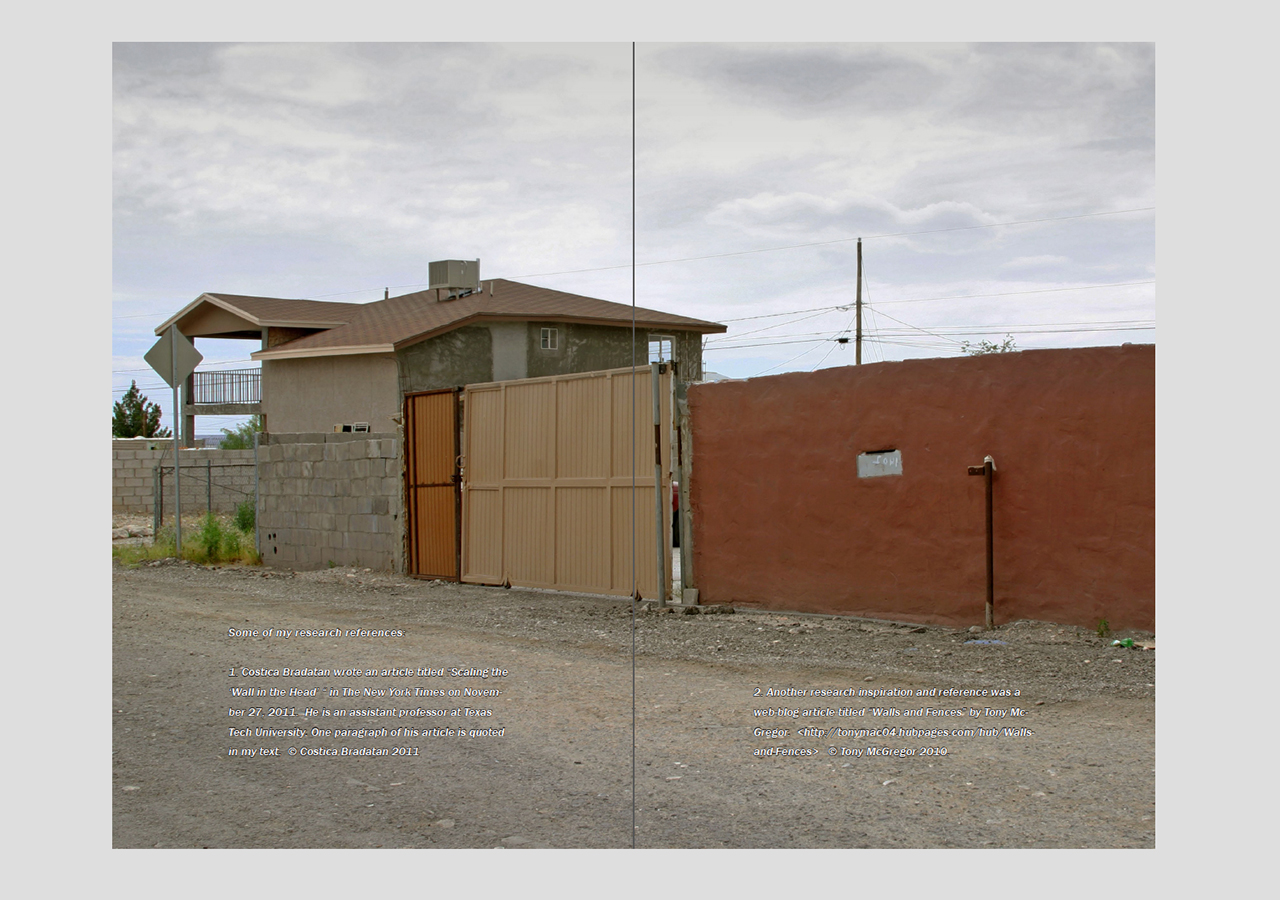

The irony is that although we as a country have spent such vast amounts of money on the fence sections that have been built, it really is not that effective. Thousands climb over weekly using ladders, tunnels, ropes, car ramps, and pure acrobatic climbing skills. It is clear that the wall is mostly an extremely expensive political and psychological construct rather than a truly effective deterrent to keeping drug smugglers and immigrants out of the United States. Are the walls and fences at Westway partially a status-symbol? Many inhabitants of Westway, with no building codes, certainly vie with their neighbors for glitzy details and height. Our Mexican border wall also has something of that: seeing the intimidating steel height of our border fence says something about how we feel about our supposed superiority as a country and our status as a desirable place where all of humanity wants to be, in effect making us a huge gated community.

To make things even more complicated, we are now entering the drone era, where for a few hundred dollars, a drone with a camera can be sent up and the resulting video image shown on a smart phone. A sense of privacy that walls and fences give is really just an illusion. Arizona is one of the national centers for drone technology and they are getting cheaper, larger, and more sophisticated all the time. As is already done in the reverse, will cheap drones allow drug smugglers and the coyotes that take immigrants over the border to spot border patrol and other surveillance personnel or equipment? It cannot be far away that drone technology will be converted back to very inexpensive manned flight. Already drones are carrying much more than cameras or even the predator missiles used in Pakistan, they are carrying crop dusting chemicals and all sorts of other heavy loads. This development indicates then that we are heading into a time that border walls will be even less of an effective deterrent to passage and far more symbolic than anything else.

So our costly border fence, still years and many more billions of dollars away from completion, is really more about politics and the sense and appearance of security rather than actual security. Dr. Bradatan, who teaches at Texas Tech University, (in another border state) also writes that “Once a wall has been erected, it acquires a life of its own and structures people’s lives according to its own rules. It gives them meaning and a new sense of direction. All those walled off now have a purpose: to find themselves, by whatever means it takes, on the other side of the wall.” He argues: “After all, history itself may be nothing more than an endless grand-scale game where some build walls only for others to tear them down; the better the former become at wall-building the braver the latter get at wall-tearing. The sharpening of these skills must be what we call progress.”

This book is only available from MagCloud as a print-on-demand book. The book is $24.95 as a perfect-bound book at <http://www.magcloud.com/browse/issue/579259>.